Mr. Lee Yong Taeck,

Director of division V, Land and Environmental Affairs Audit Division in BAI

Lee yong taeck has joined in BIA since 2005 and mainly audited about land & transport administration as well as SOC Project like audit on Light Rail Transit, Nation Rail, National harbor, Public Private Partnership(PPP) project, safety diagnosis institution and so on.

Mr. Park Jun Hong,

Director of Provincial and Local Government Audit Bureau in BAI

Park jun hong has joined in BIA since 2000 and mainly audited about land & transport administration as well as SOC Project like audit on Nation Rail, National harbor, safety diagnosis institution, construction bidding system and so on.

The Board of Audit and Inspection, the Republic of KOREA

I. Issues on Risks of Social Overhead Capital (SOC) Projects

In South Korea, SOC or Social Overhead Capital refers to some 60 types of social infrastructure, such as roads, railroads, harbors, dams, schools and social welfare facilities, which are crucial for the country. The budget allocated for such SOC projects to be carried out by both the central and local governments in 2024 is estimated to be KRW 59 trillion.

The SOC budget is often considered as discretionary spending, as it requires public agencies to make a rational judgment on whether to embark on building new SOC infrastructure or not. In other words, once started, the agencies in concern are bound to bear a significant financial burden because not only it requires a massive amount of financial investment in early stage of construction, but high operational costs are incurred over a long period of time.

In an effort to manage these risks, the government of the Republic of Korea operates a so-called Project Assurance System for SOCs, in which an independent institution checks risk factors of each stage of the SOC project. The system stands to ensure that only when risk factors of one particular stage are eliminated, can the budget for the next stage be approved.

Meanwhile, like the Government Accountability Office of the United States, the Board of Audit and Inspection (BAI) identifies high-risk areas, and examines future risks from a mid-term perspective. As of 2024, 20 high-risk areas have been identified, one of which is the “Management System for Large-scale Investment Projects, such as SOC”.

The number of SOC investments by the South Korean government is on the rise every year. However, the overall performances of the SOC projects are being undermined because: an increasing number of SOC projects are being exempted from the feasibility study, and many of them turn out to be unfortunately unviable; or are not launched as scheduled due to the delays caused by inadequate management of the project and/or numerous civil complaints.

BAI takes an active initiative in resolving these issues by conducting preventive audits within the framework of public audit system. That is to say that it identifies and removes risk factors of SOC projects for each stage before moving on to the next stage. This paper aims at introducing BAI’s audit strategies and tools for systematic examining of SOC projects with limited audit resources.

II. Issues on Risks of Social Overhead Capital (SOC) Projects

BAI’s three major audit strategies for SOC projects are as follows:

First, BAI conducts preventive audits to control risk factors of each stage of constructing SOC projects. It eradicates such risks when moving on from one stage to another, so that the problematic issues, like poor construction, budget waste, safety-related accidents, and etc. can be prevented at the following stage.

Second, BAI conducts audit primarily on those projects classified as “high-risk” after conducting quantitative and qualitative monitoring.

Third, as for those SOC projects that could not be examined comprehensively due to the constraints of audit resources, BAI utilizes the audit resources of internal audit units (IAUs) within public organizations through an established collaboration system. This is one way of reducing possible blind areas of audit.

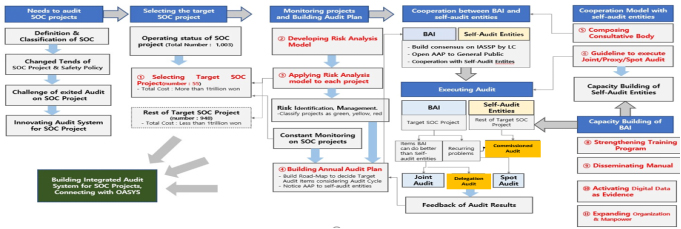

Meanwhile, in 2022, BAI has established an Integrated Audit System (IAS) for SOC projects for implementing the above-mentioned three major audit strategies, which is operated in the following matrix:

- SOC projects with a total cost of over KRW 1 trillion, or more than ten years of duration are designated as the subjects to be under direct management of BAI;

- BAI conducts an in-depth risk analysis and monitoring to classify individual SOC projects into the categories of high, medium, and low-risk. Once labeled as high-risk, it is highly likely that BAI runs an audit ;

- Since it is impractical to control multiple risk factors from numerous projects at each stage with the available audit resources, BAI takes proactive measures to prevent audit blind spots by utilizing a collaborative audit model - namely, proxy audit or outsourced audit; and

- To this end, BAI coordinates with the IAUs for designing audits from the beginning stage of annual audit planning. BAI also joins hands with IAUs in terms of their endeavors for fostering internal auditors’ capacity-development.

Figure 1. Integrated Audit System of SOC project by life cycle

Also, BAI makes use of the following audit tools to check the risks at each step of SOC projects.

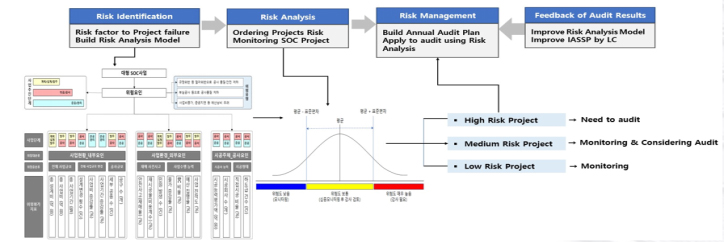

First, the Risk Analysis Model is used to quantify risk scores by inputting risk variables of individual SOC projects. Next, Analytical Hierarchy Processing is used to derive risk scores. Then, projects are categorized into high (red), medium (orange), and low (green) risk groups based on predetermined criteria, which are calculated by standard deviation of the cumulated distribution of risk scores.

Figure 2. The process of developing a Risk Analysis Model

Second, the Construction Audit Manual is used to inspect defective construction and safety management practices to be applied uniformly for multiple construction sites.

Third, Technical Audit Support Teams are constituted to enhance the quality and reliability of SOC project audits. A team of over 20 experts of bridge and building structures, railway tracks, water resources, and etc. are appointed as audit advisors to support audit activities.

Fourth, with regards to the SOC Cooperative Audit Model, BAI has been employing various types of audit methodologies in terms of composition of audit team. In order to respond in a more versatile manner to different situations of each stage of SOC projects, BAI reshuffles its audit teams at each stage to conduct either proxy audit, entrusted (outsourced) audit, or joint audit.

For example, in the designing phase, IAUs would review the appropriateness of construction costs, and request the agency to adjust the costs, if deemed necessary. But the project design department of the agency in concern would insist that the costs be increased rather for other reasons. To overcome difficulties like this, BAI employs a Cooperative Audit Model by using a technical audit support team that will anticipate possible issues and problems. Based on the analysis, BAI requests IAUs to conduct proxy audits.

For the construction phase, it is appropriate to run a joint audit because the work of construction per se can be examined only when it is underway. In other words, BAI and IAUs can separately work on discovering administrative flaws like excessive construction costs, but since checking the site requires a physical presence of auditors, BAI and IAUs compose a joint audit team to prevent overlapping and duplication, and take measures based on their own findings.

III. Conclusion

To sum up, the key lessons of the BAI’s audit system for SOC projects by life cycle can be summarized as follows.

First, to select the target project to audit, BAI has developed the Risk Analysis Model, which is to quantify risk scores of individual SOC projects. After conducting the risk analysis and monitoring, BAI runs audits for those classified as high-risk.

Second, to eliminate the risk factors of various SOC projects, which can come up at different stages, run by multiple agencies with limited audit resources, it is important for BAI to make an effort to design collaborative governance within the public audit system. To this end, BAI has established a cooperation model with the IAUs.

Furthermore, to foster active participation of IAUs, it is necessary to: build mutual trust between BAI and IAUs; discover and disseminate success cases of collaboration models; and provide the IAUs with institutional support, such as incentives for best practices.

Third, it is quintessential to make continual efforts to refine tools for designing the SOC audits - namely, the risk analysis model and collaborative audit models - to adapt to the changes in SOC policies and construction technologies.

Last but not least, BAI must not spare any efforts to support IAUs in enhancing their audit capabilities.