Juska Meidy Enyke Sjam,

Audit Director, Audit Board of the Republic of Indonesia

About the Author

Juska Sjam is currently the Director of Audit V at the Audit Board of the Republic of Indonesia. Prior, she held the position as Director of Training Planning and Implementation, Director of Public Relations and International Cooperation, and Director of Evaluation of Audit Report. Mrs. Sjam received her doctoral degree in Accounting and holds several professional certifications such as in State Finance Auditor and Data Analytics.

In Indonesia, there is a general recognition and respect for women's roles and contributions in society. In fact, the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia, which was last amended in 2002, provides a foundation for gender equality and the promotion of women's rights in the country. It upholds principles that are relevant to women's rights affirming that all citizens are equal before the law and prohibits discrimination based on various factors, including gender. Additionally, Indonesia signed international conventions and agreements related to women's rights, such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Despite the constitutional provisions and commitments, challenges remain in fully realizing gender equality in Indonesia.Over the past two decades, the Indonesian Government has developed a framework for gender equality, starting from Presidential Decree Number 9 in 2000 stipulating that “gender mainstreaming is an inseparable and integral part of the functional activities of all government agencies and institutions”, followed by the regulation of Ministry of Home Affairs Number 132 of 2003, giving a fixed allocation of 5% from the state budget for women empowerment programs managed by the Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection, a ministry that was first established in Indonesia in 1978.

But the real milestone was in 2012 when the government introduced the Gender Responsive Planning and Budgeting (GRPB) which marked the beginning of the institutionalization of gender mainstreaming. Now, gender mainstreaming is one of the four key strategies in the National Medium-Term Development Plan 2020-2024, serving as the foundation for implementing all national development programs.

What is GRPB?

GRPB is an application of gender mainstreaming in the budgetary process, involving assessment of budgets from a gender perspective, incorporating gender considerations throughout the budgetary process, and restructuring revenues and expenditures to promote gender equality.1 It encompasses several indicators and tools such as Gender Budget Statements, gender-related analysis, and audit criteria. For instance, during a fiscal training conducted by the Indonesian Ministry of Finance, the gender budget statement would record the participation of women employees in the training, and the total number of women employees trained over the past five years.2

Another example was when the Customs Directorate proposed transitioning from manual to electronic delivery for export/import document registration. While the program may appear gender-neutral, it was included in the gender budget statement and considered acceptable. Previously, manual document delivery to Customs Offices in ports often involved male workers due to safety concerns. This created a perception that export/import businesses were predominantly "male jobs." The introduction of an electronic delivery system aimed to increase women's employment in export/import firms by providing a safer and more convenient way to deliver documents. With the new system, employees could upload documents from their office, eliminating the need to physically be present at the ports.3 This gender-related analysis was acknowledged, and the program was classified as gender-responsive.

In 2016, the Indonesian National Development Planning Agency introduced a budgeting software named Krisna. Ministries, agencies, and regional governments can use the software's tagging system to identify gender-responsive programs and track their implementation and performance.

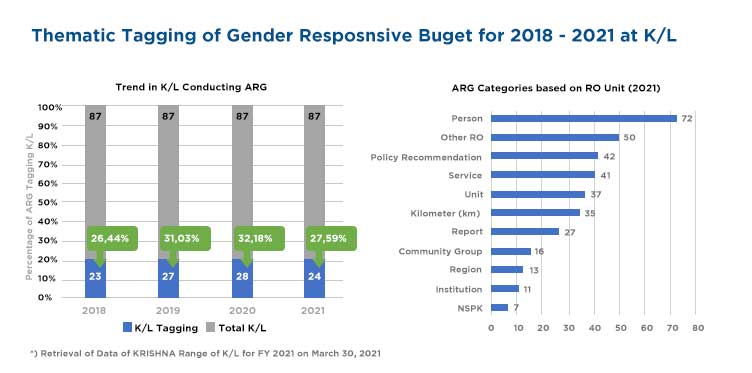

The use of Krisna and its tagging system has facilitated the integration of GRPB into Indonesia's state budget system, making it easier for the government to track the use of the state budget. For instance, in 2021, as many as 24 ministries have submitted programs under the “gender-responsive budget” tag. The system helps auditors to evaluate whether or not the gender-responsive programs achieve their objectives.

The role of audit

Audit plays a critical role as they provide accountability in the use of public funds. Traditionally, audit focuses on financial matters. But the traditional approach is not sufficient to evaluate gender-responsive programs. As stated in IDI Gender Strategy, Supreme Audit Institution (SAI) should “apply a gender lens in their organization and in their audit work”. Financial audit, while still important, is no longer sufficient to determine whether a gender-responsive program succeeds or fails. For example, the Customs Office categorized the overhaul program of export/import document delivery as "gender-responsive budget" to enhance women's employment in the sector. However, the key question remains: Did the program achieve its objectives? Did the adoption of electronic document delivery result in increased employment of women in export/import firms? These questions can be addressed through a performance audit, which would provide the necessary insights.

In Indonesia, the gender budget statement and the analysis behind the tagging of programs under a gender-responsive budget can serve as a valuable tool for auditors to apply a gender lens in their audit work. The tagging system is considered better than setting a fixed percentage of the budget for gender objectives. The previous practice of allocating a fixed percentage of the state budget on gender objectives—for example, 5% in 2003—is no longer used due to the risk of ministries spending public funds on programs without clear gender focus and labelling them as gender-responsive, for example, using public funds on ballroom dancing lesson and labelling it “gender-responsive program” as observed in some countries.4

However, the tagging system also has its limitations. Some programs with a clear impact on women might not have a gender-responsive tag because it is considered gender-neutral, for example, programs related to Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). In Indonesia, MSME’s are all about women. Data from the Ministry of Cooperatives and SMEs shows that out of 64 million people engaged in MSMEs, or 64,5%, are women.5 Consequently, programs targeted to MSMEs fall within the scope of gender-responsive programs although they are not tagged as such.

Another possible explanation for why some ministries do not categorize their programs under gender-responsive tags is the potential confusion about the tagging system. In many cases, gender objectives are only part of a larger program. When the program’s sole purpose is gender-objective such as upgrading the health facilities for pregnant women, it is straightforward and the tagging system can be used without confusion. However, if the gender objectives are only part of a larger program, such as a credit program for MSMEs or electronic delivery system for export/import document, the gender tag may not be used. Performance audit can play a crucial role to provide insight into how gender-responsive programs and the tagging system can function effectively.

A quick analysis of Krisna’s data showed that many ministries were actually “conservative” on what programs should be tagged as gender-responsive.6

Several key findings could be inferred from the data:

- In 2018-2021, in average, ministries allocated 25,5% of their budget for programs under the gender-responsive tag;

- The top output of gender-responsive programs was the number of persons receiving certain services such as training for government employees, HR development, certification, mentoring, and other services.

- The second top output of gender-responsive programs was a variety of other outputs such as MSMEs women empowerment, information system, and regulation.

Notes:

- K/L (Kementerian/Lembaga): State Ministries/Agencies

- ARG (Anggaran Responsif Gender): Gender Responsive Budget

- RO (Rincian Output): Detail Output, specific output resulted from certain program.

The term “conservative” is used because the most-tagged program under the gender-responsive tag is “training, HR development and certification for women employees”. While it is true that consistently providing an equal slot for women employees is a step towards gender equality, it does not address the more meaningful aspect of governmental administration—that is policy. However, progress is being made as indicated by the second most tagged output of ‘MSMEs women empowerment” highlighting the path towards gender equality in economic participation in Indonesia.

In a nutshell, performance audits are crucial in assessing gender-responsive programs, evaluating their effectiveness, efficiency, and impact in promoting gender equality. A few ways in which performance audits can contribute are:

- Assessing program design to determine whether programs have clear gender objectives, appropriate gender analysis, and adequate mechanisms for gender mainstreaming.

- Evaluating implementation of how well programs are implemented, the adequacy of resources allocated to gender-responsive activities, the effectiveness of implementation strategies, and the extent of coordination among different stakeholders.

- Analyzing program outcomes and impacts including whether the benefits are reaching marginalized groups of women.

- Identifying barriers and gaps in the implementation of programs, such as inadequate data collection, weak monitoring systems, or discriminatory practices.

- Providing recommendations for improvement based on audit findings.

Conclusion

The Indonesian government is committed to building a strong framework for gender equality by integrating gender-responsive programs into the state budget system. However, further efforts are needed to raise awareness and support for the GRPB across government agencies. Performance audit serves a crucial tool to assess the country’s progress on gender issues and the effectiveness of achieving gender objectives.

1 “What is gender budgeting?”, European Institute for Gender Equality.https://eige.europa.eu/gender-mainstreaming/toolkits/gender-budgeting/what-is-gender-budgeting (Accessed on May 2023).

2 Ministry of Finance, gender budget statement 2018.

3 Directorate General of Custom, gender budget statement 2018.

4 Overview of Gender Responsive Budget Initiatives, ILO discussion paper. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---gender/documents/publication/wcms_111403.pdf (Accessed on May 2023).

5 “Kemenkop UKM: 64,5% Pelaku UMKM Didominasi Perempuan”, antaranews.com, December 22, 2021. https://www.antaranews.com/berita/2600565/kemenkop-ukm-645-persen-pelaku-umkm-didominasi-perempuan (Accessed on May 2023).

6 Bappenas, Policy, Implementation and Challenges of PUG and PPRG (Gender Mainstreaming and GRPB), presentation slide.