About the Author

By Minjung KIM

(Division1, Bureau of Land, Transport and Maritime Affairs Audit)

1. Introduction

The occurrence of quarantinable communicable diseasesis rare, but it can cause disastrous results if not controlled at an early stage, which means thatthe health authority’s early response is of the utmost importance. With growing concerns over the possible importation of overseas infectious diseases in recent years, such as the Novel Coronavirus and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV), it has becomecritical for the government to prepare effective response measures to protect its people.

Accordingly, the Korean governmentupgraded its system to prevent and control infectious diseases by formulating the “Measures to Reform National Infection Prevention and Control System” in September 2015.Also, the related budgetwas increased from KRW 40.7 billion in 2015 to 349.4 billion (through a supplementary budget in 2015), and the annual budget on average from 2016 to 2018 was KRW 95.5 billion.

In this context, the Korean government has been giving its best to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic by establishing an advanced quarantine system, the “K-Quarantine Model,”which consists of three stages: Testing, Tracing and Treatment (3T).This model aimstobalancedailylifewith containment efforts by (1) providing convenienttesting anytime and anywhere, (2) enhancing containment of virus spread through rapidtracingof those who were in contact with an infected person, and (3) providing rapid treatmentthrough sufficient availability of healthcare workers and treatment facilities.

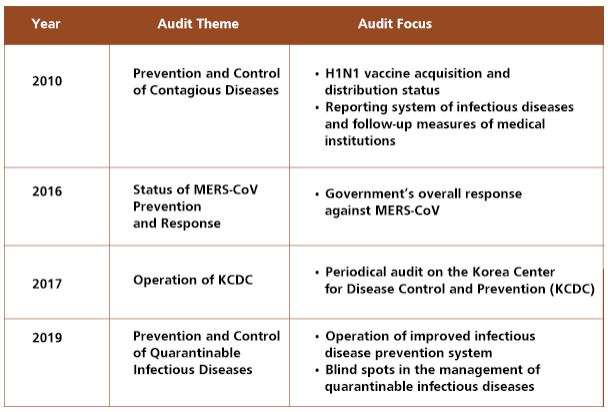

As a result, Korea ranked second in the index for efficient response to COVID-19 among the 33 OECD member countries and is regarded as one of the topcountries whose economic growth rate remains high while containing the spread of the virus; Korea has limited theCOVID-19 damage to a 1% GDP contraction in 2020 while the United States and European Union GDP shrank by 3.9% and 7.2%, respectively, in 2020. The OECD stated in August 2020 that Korea has been successful in minimizing the economic impact from the COVID-19 crisis with swift and effective measures to contain the virus, and the WHO also stated in October 2020 that Korea has showed the possibility of effective control of COVID-19. From 2010 to 2019, the Board of Audit and Inspection (BAI) has conducted four audits relating to infectious diseases to find the obstacles in securing an effective management system and suggest measures for improvement. The audits checked if the infrastructures for quarantine (including the Smart Quarantine Information System, negative pressure ambulances, etc.) were being operated effectively and examined whether the infectious disease prevention system was being systematically operated.The BAI’s audits are considered to be one of the components of the government’s effective and agile responses to COVID-19.

2. Objective and focus

The conventional infectious disease surveillance system had focused on entry screening.The old-fashioned strategy to respond to the infectious disease had been focused on entry screening at the airports and harbors as the incubation period of conventional diseases had been relatively short (e.g. five days for cholera) and the travel time was not too short to revealthe symptomsat the border control stage. As the novel infectious viruses tend to have a longer incubation period (e.g. 21 days for Ebola virus and 14 days for MERS-CoV) and become more contagious, the government’s response strategy faced limitations. As such, the Korean government upgradedits system to prevent and control infectious diseases, and the BAI conducted four audits focusing on the overall response measures against quarantinable communicable diseases from 2010 to 2019.

3. Major findings and recommendations

A. Effective Utilization of Health Care Workers and Medical Facilities

The KCDC is responsible for stockpiling and managing vaccines and antiviral drugs to cope with novel infectious diseases, and regarding this, the BAI found several problems. One of the problems was that the KCDC stockpiled smallpox vaccines that had not been approved by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. In addition, the KCDC purchased the H1N1 vaccine securing doses for only 2.5 million people, half of the originally planned amount as of April 2009. This was due to the KCDC requesting a smaller amount of budget for the vaccine purchase than the actual amount they needed. In this regard, in 2010, the BAI demanded the KCDC to purchase necessary vaccines and antiviral drugs at an appropriate level, manage the stockpiles of them, and ensure the quality of the stockpiles.

Since the outbreak of MERS-CoV in 2015, the KCDC had implemented a plan to recruit more epidemiological investigators to effectively prevent disease transmission early on. In 2016, the BAI found, however, that the epidemiological investigators worked eight hours (from 9am to 6pm) a day at major airports. For the rest of the day, the airports operated without epidemiological investigators, despite the fact that around 40% of all flights arrived between 6pm to 9am the following day. In response, the BAI demanded the KCDC to come up with measures that year to maintain a 24-hour quarantine system for all major airports.

In 2016, the Ministry of Health and Welfarepurchased 30 negative pressure ambulances to prevent infection during the transfer of patients. Among 30 institutions receiving the ambulances, however, quarantine centers and local public healthcare centers in charge of patient transport were excluded, while 16 ambulances were assigned to some general medical institutions that were not equipped with infectious disease treatment beds.As a result, only three patients were transferred by negative pressure ambulances to medical institutions by the year 2018. The BAI requested the health authorities to take corrective measures, such as relocating the ambulances to appropriate medical institutions, to ensure that the ambulances are effectively and efficiently used to transport patients with infectious diseases.

B. Strict Operation of Quarantine and Prevention System to Control Infectious Diseases

To prevent the inflow of emerging infectious diseases and to protect people from domestic and global health threats, the KCDC designated“quarantinable disease risk areas” and conducted quarantine inspections on passengers (both nationals and foreigners) traveling from high-risk areas. In 2016, however, Southeast Asian countries, such asVietnam, were not designated as risk areas for the Zika virus, nor were Lebanon and Bahrain designated as risk areas for MERS-CoV. In this regard, the BAI demanded the KCDC to timely update the designation of risk areas using information on the occurrence of infectious diseases.

For cases where passengers experience suspected symptoms of infectious diseases during the quarantine phase, officials at the National Quarantine Station (NQS) should notify the list of suspectedpassengers to the local public healthcare centers so as to keep the suspected cases under surveillance. However, the BAI found that 639 people were omitted from the tracing list from January 2017 to September 2018, and with regards to this,the BAI demanded the KCDC and the NQS to be strict on monitoring and tracing suspected cases.

Since the outbreak of MERS-CoV in Korea in 2015, the KCDC operated the Smart Quarantine Information Systemwhich links to passport information, immigration records and information of individuals from “quarantine inspection required areas,” to find and monitor those entering South Korea after either staying in or passing through “quarantinable disease risk areas.” Since April 2017, the KCDC was able to find and trace those entering Korea via a third country after visiting quarantinable disease risk areas through roaming records of mobile carrier companies, but did not utilize such information. As a result, only 3.2% of entrants arriving from quarantinable disease risk areas via a third country received a quarantine inspection in 2018. In this regard, the BAI demanded the KCDC to effectively and efficiently utilize the Smart Quarantine Information System.

The medical institutions are required to report confirmed and suspected infectious disease patients to the local public healthcare centers and/or the KCDC, but they only requested medical expenses for the treatment of infected patients to the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) without reporting to the health authorities. From 2016 to 2018, 400 out of 681 patients with the Zika virus were not reported to the health authorities. Through various audits, the BAI has repeatedly asked the KCDC to thoroughly supervise medical institutions, for instance, by checking whether patients suspected of infection have been reported using data of medical expenses paid by the NHIS to medical institutions.

C. Government’s Response to MERS-CoV

Since the first MERS-CoV case was confirmedin South Korea on May 20, 2015, a total of 186 cases were reported, of which 36 cases resulted in death. Despite the high fatality rate (almost 20%), the government delayed disclosing information such as transmission routes of confirmed patients and the hospitals affected by MERS-CoV. This only instigated fear among people and caused an economic recession thatresulted in a KRW 4 trillion drop in GDP in 2015. The BAI conducted an audit to assess the government’s overall response to MERS-CoV and to analyze the factors contributing to the initial spread.

The KCDC downplayed the severity of the virus despitetheWHOissuing eight separate alerts regarding MERS-CoV. The KCDC did not conduct a diagnostic test until 34 hours after receiving a report on the first suspected case. Even worse, patient #14 (superspreader) and other patients who had come into contact with patient #1 were missing from the contact tracing list. They should have been quarantined, but had visited other hospitals even though they had fever symptoms, resulting in a massive secondary transmission (one patient infected up to 83 people). Although the KCDC knew that its initial response failed, they did not take immediate proactive and corrective actions and/or measures to prevent the widespread of the virus. The KCDC refused to disclose the names of the hospitals exposed to MERS-CoV until June 7. It was also found that the list of 678 people who had come into contact with patient #14 was provided to the KCDC on June 2, but was not shared with the municipal/provincial public health centers until June 7. Due to the delay in the contact list being released, 40 out of 687 people were diagnosed with MERS-CoV (though they were not recognized as close contacts), and of them six died.

To treat patients with respiratory infectious diseases (from 2006 to 2010), the KCDC provided financial support to 19 hospitals to operate 599 infectious disease specialty sickbeds, including 119 negative pressure beds. Among the 119 negative pressure beds, 79 beds were put in multiple-occupancy rooms. However, in cases where more than two beds were in the same room, only one bed was utilized for patient accommodation in order to prevent contamination between patients in the same room. When introducing negative pressure beds, it was not required for hospitals to have an infectious disease specialist. As such, three out of 19 hospitals installed negative pressure beds without specialists who can treat patients with infectious diseases. Altogether, this caused inefficiencies in utilizing the negative pressure beds.

The BAI recommended the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the KCDC to implement comprehensive preventive measures for infectious disease, to disclose accurate information such as the contact lists for tracing and the names of hospitals affected by the infectious diseases, as well as to prepare improvement measures to utilize resources and facilities in an effective and efficient manner.

4. Conclusion

The BAI’s audit activities related to the infectious diseases from 2010 to 2019 have helped the health authorities to secure necessary resources and facilities, as well as to improve the quarantine and prevention systems; the BAI’s audits are considered one of the components of the government’s effective and agile responses to COVID-19. The BAI will continue to support quarantine operations while monitoring the health authorities’ work in the field. It will also continue to cooperate with other Supreme Audit Institutions by sharing audit methods and experiences in supporting the governments’ response to prevent the spread of infectious diseases.