Ms. Chandra Puspita Kurniawati is an analyst in BPK. She is currently pursuing her Master’s degree at Padjadjaran University, majoring in public policy. She has been involved in several INTOSAI projects related to developing disaster-related audit guidance and research related to auditing disaster preparedness.

E-mail: chandra.kurniawati@bpk.go.id

Disaster management corresponds to gender issues in significant ways. Therefore, minimizing the impacts of disasters cannot be carried out by disaster-based actions alone. Policies governing disaster management activities have the potential to either reinforce gender differences or contribute to improving gender equality. And thus, employing normative legal research, this study tries to identify how Indonesian disaster management law considers gender equality in its articles. The study finds that Law No. 24 of 2007 has not taken into consideration gender equality-related issues sufficiently. This can be seen from the absence of articles that govern gender equality in disaster management activities; mandate the inclusion of gender equality in institutional arrangement, disaster management entities, and policy formulation; emphasize preparation of disaggregated data and information that is gender sensitive; as well as raise awareness about building women’s capacity to cope with disasters. The law also neglects gender-related issues in the fulfillment of basic needs for disaster victims and excludes women from prioritized vulnerable groups. Thus, this study recommends relevant in-charge parties re-visit the disaster management law to accommodate the essential issues of gender equality.

Keywords: disaster management; gender equality; policy

IntroductionDisasters are commonly assumed to be gender-neutral. However, some perceive that disasters are gendered events since their impacts and consequences are not gender-blind (Bradshaw & Fordham, 2015). Moreover, during an emergency, disparities may be evident. Gender-specific barriers, such as tradition, cultural norms/restrictions, stereotypes, male-female dichotomy, gender-specific skills and behaviors, discrimination, as well as socioeconomic status, may make women experience disasters in a different way than men (The World Bank (2012); (Schwerhoff & Konte (2020)). Moreover, women have specific interests and needs before, during, and after disasters (Gokhale, 2008). All those aforementioned conditions then create inequalities which are believed to be the root cause of women’s disaster vulnerability.

When a disaster strikes, everyone is indeed vulnerable to becoming a victim of the disaster. However, several disasters have indicated that there is a prominent discrepancy in deaths between men and women. A study carried out by Neumayer & Plümper (2007), for example, revealed that women were impacted more adversely by disasters causing women more likely than men to die in disasters. Besides, in the aftermath of disasters, gender-based violence was exacerbating and still life-threatening for women and girls (KPPPA - UNFPA, 2020).

In addition, more than half of districts/cities in Indonesia experience disasters every year (UNDRR, 2020). In other words, the more intensity and frequency of disasters, the threats of loss of life and gender-based violence are greater, and women, especially from marginalized groups, have the greatest vulnerability to these threats. Therefore, treating men and women as homogeneous groups when dealing with disasters can be problematic. And thus, this issue should be addressed accordingly by policy-makers through the adoption of appropriate policies. This means policy-makers should consider ways in which intersecting identities and gender influence disaster impacts in any given area before making decisions on policy, to be able to mitigate gendered differences in disaster outcomes and optimize advantages for all.

Indeed, the need to address disaster and the need to eliminate gender inequality are linked. Although failing to integrate gender throughout the Hyogo Framework for Action itself, the framework has, at least, paid attention to gender by stating in its opening section that a gender perspective should be integrated into disaster management policies, plans, and decision-making processes. On the other hand, focusing events can propel issues onto the policy agenda, especially when they reinforce some preexisting perception of a problem. Hence, its successor, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, recognizes the significant roles women play in all phases of disaster management. The framework also emphasizes the need for enhancing women’s leadership in promoting universally accessible response, recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction approaches.

Meanwhile, in responding to multidimensional crises in Indonesia, Law No. 24 of 2007 on Disaster Management has been stipulated. This law serves as a policy umbrella and guidance for disaster management activities in Indonesia at all phases, both at the national and local levels. Moreover, Sadiawati et al. (2019) state that public policy in the form of laws and regulations is an important element in state law to carry out efforts to achieve national goals as well as provide legitimacy and legality for government actions. Consequently, failure to create good laws and regulations will be counterproductive and result in less performance of state administration. Hence, considering the serious impacts disasters create on the achievement of SDGs as well as the government's goal to fight for gender equality in all fields, it is important to ensure that the policy framework for disaster management has taken into consideration issues affecting the success of disaster management, including gender equality issue. Accordingly, this study will identify how Law No. 24 of 2007 accommodates gender perspectives in its articles. Subsequently, this study will provide input for relevant in-charge parties to revise the existing policy framework to include missing issues related to gender equality.

Research MethodThis study employs normative legal research. Normative legal research is a study that tends to view law from the perspective of its norms (Soekanto in Sonata, 2014). Purwati (2020) adds that normative legal research examines written rules and regulations from philosophy, history, theory, comparison, scope and material, composition and structure, general explanation and chapter by article, and language used. In terms of data, Soekanto & Mamudji (2001) stated that normative legal research is similar to literature study due to the dominant utilization of secondary data. This study uses Law No. 24 of 2007 on Disaster Management as primary legal material and other relevant written documents as secondary legal materials, such as articles from scientific journals, books, and other related sources.

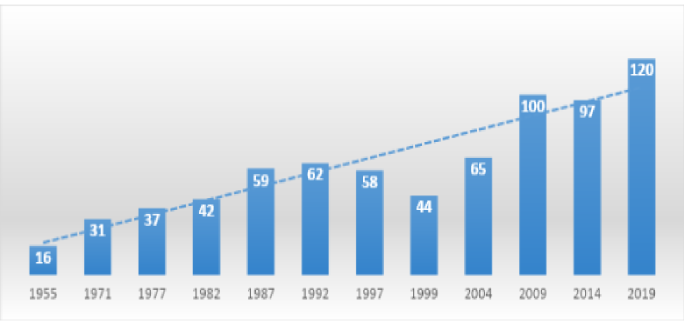

Result and Discussion Women’s involvement in disaster management policy makingAddressing gender inequalities by enhancing female participation in decision-making is crucial. Therefore, having a significant percentage of women engaged in decision-making can improve policy concerns on gender equality since women understand what women need better. Unfortunately, female participation in the Indonesian political agenda is relatively low. Actually, Article 245 Law No. 7 of 2017 on General Election has mandated at least 30% of representation of women in Parliament. Although the representation of women in the Parliament shows an increasing trend (as indicated in Figure 1), the representation of women resulting from the 2019 general election has only reached 20.87% of the total members of the Parliament. It makes masculinity dominates policy-making in Indonesia, run by officials and experts with male background and patriarchal paradigm. Commission VIII that prepared the Disaster Management Bill, for example, only has 13 female members out of 49 members (26.53% of representation of women). Fewer women involved in this policy-making process result in negative consequences reflected in the policy products that are not gender friendly to vulnerable groups nor answer to women’s needs.

Figure 1. Number of representation of women in Indonesian Parliament

Source: https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/2022/06/20/tren-jumlah-anggota-dpr-ri-perempuan-kian-meningkat (accessed on May 1st, 2023)

Gender equality in Law No. 24 of 2007Law No. 24 of 2007 consists of 13 chapters and 85 articles. This law covers the general definition; basis, principles, and goals of disaster management; roles and responsibilities; institutional arrangement; community’s rights and obligations in disaster management; roles of business players and international organizations in disaster management; disaster management activities; disaster relief funding and management; supervision; dispute resolution; criminal provisions; transitional provisions; and closing.

Referring to the law, when discussing the definition of disaster, a disaster tends to be measured in terms of loss of life, economic output, and infrastructures which are commonly measured immediately after a disastrous event. However, when seeing the definition of disaster using a gender perspective, the discussion should shift into “what is the real disaster”, especially for women and girls. Bradshaw & Fordham (2015), for example, show that in the aftermath of a disaster, women and girls may feel intangible changes, such as the impact of gender-based violence, psychosocial impact, deterioration in reproductive and sexual health, poverty and insecure employment, and so on. Some women and girls may perceive those intangible changes as a disaster. Therefore, policy makers should be very careful in formulating the definition of disaster, including the definition of disaster management phases, to include and consider issues related to gender equality.

Besides, of many topics governed by Law No. 24 of 2007, there is only one word of gender found, i.e. in the elucidation of Article 3 paragraph 1 letter c concerning the principle of equality in law and government. In this case, equality in law and government means disaster management should not contain materials that differentiate people’s background, among others, religion, ethnicity, race, gender, and social status. Even though this paragraph has implicitly mandated disaster management actors to take into account gender equality in disaster management, this spirit is not mainstreamed throughout the law.

Furthermore, gender equality has not been taken into account in the chapters or articles related to institutional arrangement, disaster management entities, and policies. Articles dealing with the roles and responsibilities of the central government, local government, as well as National and Local Disaster Management Agencies do not address gender issues at all. For example, Article 7 paragraph 1 letter a only mandates the government and National Disaster Management Agency to formulate disaster management policies that are aligned with development plans and policies. This article does not mandate the inclusion of gender perspective in the formulation of disaster management policies. Further, Article 13 only mandates the National Disaster Management Agency to formulate disaster management policies and deal with refugees timely, efficiently, and effectively. This article does not concern gender issues when dealing with refugees nor mandates the National Disaster Management Agency to take into account gender equality in its policies. Moreover, in the articles referring to steering committee membership and chairmanship of National and Local Disaster Management Agencies, there is also no mandatory requirement to include women representation.

Realizing the absence of laws and regulations related to gender mainstreaming in disaster management, the National Disaster Management Agency issued Regulation of the Head of National Disaster Management Agency No. 13 of 2014 concerning Gender Mainstreaming in Disaster Management. Even though this regulation has required government, local government, and non-government parties to mainstream gender in disaster management-related policies, activities, programs, and projects, the National Disaster Management Agency may find some constraints when monitoring and enforcing the implementation of this policy. Moreover, it may be difficult for this low level of statutory provision to ensure that gender equality has been considered in access, participation, decision-making, and policies/programs/projects’ benefits since disaster management activities are cross-sectoral, cross-jurisdictional and cross-powers and carried out by all inline ministries in central level and local working units in the local level.

Furthermore, there are several articles dealing with data preparation, such as Article 36 paragraph 3 (data for disaster risk reduction activities), Article 45 paragraph 2 letter f (data for disaster preparedness activities), and Article 54 (data for emergency response activities). However, none of those articles emphasizes the preparation of disaggregated data and information that is gender sensitive. This results in the related entities do not hold data disaggregated by gender, not because they do not choose to or are unaware of the need for such data, but merely because the organizations who provide data for the database do not collect it. For example, the audit carried out by SAI Indonesia revealed that there is a serious problem regarding the implementation of training programs which are intended to build state apparatuses and relevant in-charge parties capabilities to compile and prepare gender-based data. Although the audit focused on the accountability of budget utilization and the use of stimulant funds (BPK RI, 2010), the audit results implied that the failure of training implementation in several regions indicated the government’s insufficient attention both to the importance of state apparatuses and relevant in-charge parties capabilities to compile and prepared gender-based data and the data themselves. Besides, the law has mandated the preparation and fulfillment of goods and services for disaster victims. However, the articles neglect gender-related issues in the fulfillment of basic needs for disaster victims. The preparation of homogeneous and generalized basic needs may put women and girls at risk. For example, several gender-based violence cases were reported where many women and girls had been victims of rape and sexual harassment in Aceh in 2004 (UNIFEM in KPPPA, 2011), Central Sulawesi in 2018 (UNFPA, 2019), and Lombok West Nusa Tenggara in 2018 (KPPPA - UNFPA, 2020). The cases occurred when they were living in refugee and displacement camps where protection and privacy were often inadequately addressed. Moreover, the law also excludes women from priority groups, particularly when dealing with rescue, evacuation, in addition to health and psychosocial services. The law put special attention only to the elderly, people with disabilities, children, as well as pregnant and breast-feeding mothers (see Article 26 paragraph 1 letter a).

In addition, when dealing with capacity building, the gender equality issue is completely left behind. Although many studies have indicated women’s disaster vulnerability, there are no capacity-building programs that target women in particular. Simply allocating more aid to women to reduce their vulnerability only addresses the symptoms but not the cause.

ConclusionGendered differences in a disaster can influence disaster management activities. Thus, policies that focus on reducing gender inequalities will mitigate disaster impacts more efficiently without exacerbating existing gender gaps. In this case, the policy-makers’ understanding of problems causing gender differences in vulnerability to disasters will help to identify comprehensive policy options for addressing both disaster management and gender inequality.

Unfortunately, a critical study of Law No. 24 of 2007 reveals that this law has not taken into account gender perspective in its articles in the most favorable way. In other words, the intent of incorporating a gender perspective into this high-level legislation to ensure that the concerns of all and that gender inequalities are addressed are not perpetuated through institutional means. Consequently, the derivative policies and practices designed to deal with disasters, at all phases, lack attention to gender equality in particular.

Disaster management policy needs to be conscious of the power relations between women and men, both existing and newly created ones. These dynamics are constantly evolving and can be directed in a more cooperative and fair direction. Gender mainstreaming of disaster management policy is the most explicit method of doing this. The synergy effects of gender equality on disaster management policy, and vice versa, can be reinforced intentionally to achieve both objectives simultaneously. Therefore, the revision of the Law on Disaster Management should be viewed as an opportunity to address gender inequality issues and promote women's rights.

ReferencesBPK RI. (2010). Compliance Audit Report on Expenditure at Ministry of Women’s Empowerment (Fiscal Year 2008 and First Semester of 2009).

Bradshaw, S., & Fordham, M. (2015). Double Disaster: Disaster through a Gender Lens. In Hazards, Risks and, Disasters in Society (pp. 233–251). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-396451-9.00014-7

Gokhale, V. (2008). Role of Women in Disaster Management: An Analytical Study with Reference to Indian Society. The 14th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, 1–8.

KPPPA. (2011). Gender dalam Bencana Alam dan Adaptasi Iklim.

KPPPA - UNFPA. (2020). Pedoman Perlindungan Hak Perempuan dan Anak dari Kekerasan Berbasis Gender dalam Bencana (2nd ed.). Kementerian Pemberdayaan Perempuan dan Perlindungan Anak.

Neumayer, E., & Plümper, T. (2007). The Gendered Nature of Natural Disasters: The Impact of Catastrophic Events on the Gender Gap in Life Expectancy, 1981-2002. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 97(3), 551–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00563.x

Purwati, A. (2020). Metode Penelitian Ilmu Hukum: Teori dan Praktik (T. Lestari (ed.)). CV Jakad Media Publishing.

Sadiawati, D., Sholikin, M. N., Nursyamsi, F., Damayana, G. P., Argama, R., Rofiandri, R., Putra, A., Astarina, N. T., Maolana, M. I., Akbar, Y. W., & Destianissa, M. (2019). Kajian Reformasi Regulasi di Indonesia: Pokok Permasalahan dan Strategi Penanganannya (Cet.1). Yayasan Studi Hukum dan Kebijakan Indonesia.

Schwerhoff, G., & Konte, M. (2020). Gender and Climate Change: Towards Comprehensive Policy Options. In M. Konte & N. Tirivayi (Eds.), Women and Sustainable Human Development: Gender, Development and Social Change (pp. 51–67). https://doi.org/https://doi.or/10.1007/978-3-030-14935-2_4

Soekanto, S., & Mamudji, S. (2001). Penelitian Hukum Normatif: Suatu Tinjauan Singkat. RajaGrafindo Persada. Sonata, D. L. (2014). Metode Penelitian Hukum Normatif dan Empiris: Karakteristik Khas dari Metode Meneliti Hukum. Fiat Justicia Jurnal Ilmu Hukum, 8(1), 15–35.

The World Bank. (2012). Making Women’s Voice Count: Integrating Gender Issues in Disaster Risk Managemeny. UNDRR. (2020). Disaster Risk Reduction in Indonesia: Status Report 2020 (A. Perwaiz, J. Parviainen, P. Somboon, A. Mddonald, A. Kumar, T. Wilcox, I. T. Calle, & O. Amach (eds.)). UNDRR, Regional Office for Ais and the Pacific. https://www.undrr.org/publication/disaster-risk-reduction-india-status-report-2020

UNFPA. (2019). Terjadi Kekerasan Seksual dalam Masa Darurat Sulawesi Tengah. Antaranews.Com. https://sulteng.antaranews.com/berita/74572/unfpa-terjadi-kekerasan-seksual-dalam-masa-darurat- sulawesi -tengah