Mr. Dinesh Bhargav,

Government Accounting Standard Advisory Board (GASAB) Email :bhargavd@hotmail.com, Phone : +917869611134

About the Author

The author is 1990 batch IAAS Officer. Ever since joining this service, he has held several executive level posts within the organization and holds more than 20 years of experience in the areas of auditing & accounting, finance and administration. Audit experience pertains to 3 areas of audit viz. compliance audit, financial attest audit and performance audit of the government departments and public sector undertakings. At the international level, the author has supervised the audit team conducting the audit of Indian mission in countries viz. Algeria, Libya, Nigeria (Abuja &Lagos) and Saudi Arabia where significant audit observations were raised and reported to the concerned ministry for further improvement and corrective action. In the year 2021, he conducted Compliance Audit of FAO’s (UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, Rome) Sub-regional office, Zimbabwe and Country offices of Cameroon, Malawi and Zimbabwe. The audit was successfully conducted remotely due to travel restriction of Coronavirus pandemic.

The officer has done MBA(Finance) from Amity University. He is currently posted in Government Accounting Standard Advisory Board in CAG’s office, a body which advises Government on forms of accounts under Article150 of the Constitution of India.

1 Introduction

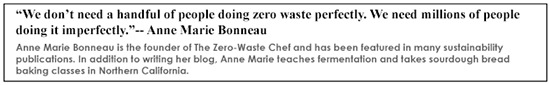

Plastic products have become an integral part of our daily life as a result of which the polymer is produced at a massive scale worldwide. On an average, production of plastic globally crosses 150 Million tonnes per year. A report by the United Nations in 2020 found that “the global material footprint grew from 73.2 billion metric tons (mt) in 2010 to 85.9 billion mt in 2017, involving increase by 17.4 per cent”. Rising population, urbanization, modern lifestyle, human development and wellbeing are the biggest drivers of consumerism and economic growth in contemporary times. Its broad range of application is in packaging films, wrapping materials, shopping and garbage bags, fluid containers, clothing, toys, household and industrial products, and building materials. Unsustainable consumption and production patterns along with increasing waste and emissions has contributed to various environmental concerns. While some kinds of plastic do not decompose at all, others could take up to 450 years to break down. The figure below captures per capita plastic consumption in FY 2014-15:

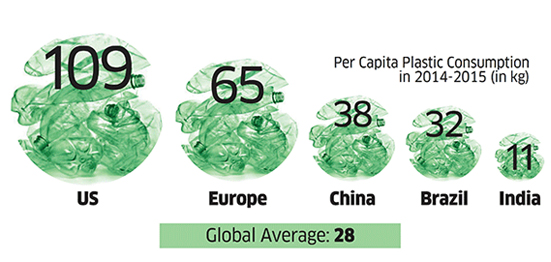

Annual Plastic Emission by 2050:

1.2. Plastic as a boon

Plastics are not inherently bad, and they have many redeeming ecological features. Many of the techniques we utilize in our designs involve targeted use of plastic products. Their durability and low maintenance reduce material replacement, their light weight reduces shipping energy, their formulation into glue products allows for the creation of engineered lumber and sheet products from recycled wood, and their formulation into superior insulation and sealant products improves the energy performance of our structures. Once plastic is discarded after its utility is over, it is known as plastic waste. It is a fact that plastic waste never degrades, and remain on landscape for several years. Mostly, plastic waste is recyclable but recycled products are more harmful to the environment as this contains additives and colors. The recycling of a virgin plastic material can be done 2-3 times only, because after every recycling, the plastic material deteriorates due to thermal pressure and its life span is reduced. Hence recycling is not a safe and permanent solution for plastic waste disposal. It has been observed that disposal of plastic waste is a serious concern due to improper collection and segregation system.

1.3. Plastic as a bane

Plastic is versatile, lightweight, flexible, moisture resistant, strong, and relatively inexpensive. Those are the attractive qualities that lead us, around the world, to such a voracious appetite and overconsumption of plastic goods. However, durable and very slow to degrade, plastic materials that are used in the production of so many products, ultimately, become waste. Our tremendous attraction to plastic, coupled with an undeniable behavioral propensity of increasingly over-consuming, discarding, littering and thus polluting, has become a combination of lethal nature.

The disposal of plastics is one of the least recognized and most highly problematic areas of plastic’s ecological impact. Ironically, one of plastic’s most desirable traits: its durability and resistance to decomposition, is also the source of one of its greatest liabilities when it comes to the disposal of plastics. Natural organisms have a very difficult time breaking down the synthetic chemical bonds in plastic, creating the tremendous problem of the material’s persistence. A very small amount of total plastic production (less than 10%) is effectively recycled; the remaining plastic is sent to landfills, where it is destined to remain entombed in limbo for hundreds of thousands of years, or to incinerators, where its toxic compounds are spewed throughout the atmosphere to be accumulated in biotic forms throughout the surrounding ecosystems

1.4. Groundwater and soil pollution

Plastic is a material made to last forever, and due to the same chemical composition, plastic cannot biodegrade; it breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces. When buried in a landfill, plastic lies untreated for years. In the process, toxic chemicals from plastics drain out and seep into groundwater, flowing downstream into lakes and rivers. The seeping of plastic also causes soil pollution and have now started resulting in presence of micro plastics in soil.

1.5. Pollution in Oceans

The increased presence of plastic on the ocean surface has resulted in more serious problems. Since most of the plastic debris that reaches the ocean remains floating for years as it does not decompose quickly, it leads to the dropping of oxygen level in the water, severely affecting the survival of marine species. Materials like plastic are non-degradable which means they will not be absorbed and recycled. When oceanic creatures and even birds consume plastic inadvertently, they choke on it which causes a steady decline in their population. The harmful effects of plastic on aquatic life are devastating, and accelerating. In addition to suffocation, ingestion, and other macro-particulate causes of death in larger birds, fish, and mammals, the plastic is ingested by smaller and smaller creatures (as it breaks down into smaller and smaller particles) and bio accumulates in greater and greater concentrations up the food chain—with humans at the top. Even plankton, the tiniest creatures in our oceans, are eating micro plastics and absorbing their hazardous chemicals. The tiny, broken down pieces of plastic are displacing the algae needed to sustain larger sea life who feed on them. Some important facts about plastic are as under:

- Plastics are made from oil with a highly polluting production process. Plastics just do not dissolve; they break down into micro-particles that circulate in the environment. A single water bottle can take up to 1000 years to break down.

- Asia is the world leader in plastic pollution. The Philippines alone dumped over 1 billion pounds of plastics into our oceans. That is over 118,000 trucks worth. In 30 Years there is likely to be more plastic in our oceans than fish. 83% of our drinking water contains plastic. Studies show that consuming plastic could lead to cancer, effects on hormone levels, and heart damage. Plastics have been found in the blood of even new born babies.

- Over 600 marine species are affected by plastics. Nearly 45000 marine animals have ingested plastics and 80% were injured or killed. Plastics can pierce animals from inside or cause starvation, entanglement, loss of body parts and suffocation.

- As plastics travel with ocean currents, an island of trash called the “Great pacific Garbage Patch” has been created. There are now many islands of trash in our seas.

Figure: Whale killed by plastic waste

1.6. Dangerous to human life

Burning of plastic results into formation of a class of flame retardants called as Halogens. Collectively, these harmful chemicals are known to cause the following severe health problems: cancer, endometriosis, neurological damage, endocrine disruption, birth defects and child developmental disorders, reproductive damage, immune damage, asthma, and multiple organ damage.

2. Global response to global crisis

There is clarion call by the world community to find sustainable solution to crisis. Steps have been taken at various levels-World Organisations, National governments of the respective country, Civil society, Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) and other Stakeholders towards mitigation of crisis as given below:

2.1. UN’s Initiative:

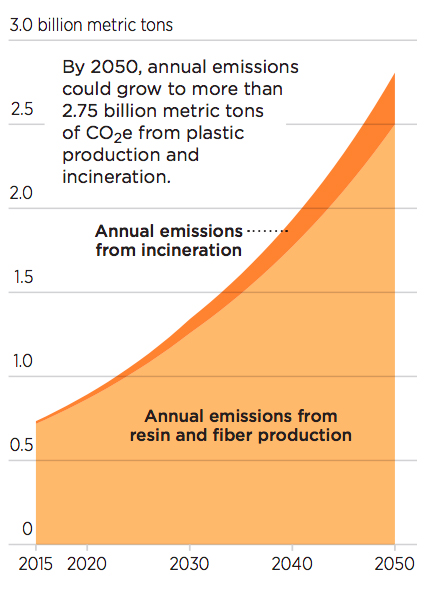

In 2019, United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) recognized plastic waste crisis as a serious and rapidly growing issue. With the objective of significantly reducing manufacture and use of single-use plastic products by 2030, mem¬ber states adopted a Ministerial Declaration titled ‘Innovative Solutions for Environmental Challenges and Sustainable Consumption and Production’ at the end of UNEA session (2019.). Further, Heads of State, Ministers of environment and other representatives from UN Member States endorsed a historic resolution at the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA-5) March 2022 in Nairobi to end Plastic Pollution and forge an international legally binding agreement by 2024. The resolution addresses the full lifecycle of plastic, including its production, design and disposal. The 17 SDGs were set up in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly and are intended to be achieved by 2030. SDG 12 concerning SCP, underpins every other SDG. SDG 12 aims to ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns, champions this theme and believes in sustainable lifestyles by increasing resource efficiency and reducing environmental degradation, as depicted in Figure below:

Targets of SDG 12

YFP: Year Framework of Programme; SCP: Sustainable Consumption and Production PRRR: Product Reduction, Recycling, and Reuse; DCs: Developing Countries

2.2. India's Initiatives

India: According to the reports for year 2017-18, Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) has estimated that India generates approximately 9.4 Million tonnes per annum plastic waste, (which amounts to 26,000 tonnes of waste per day), and out of this approximately 5.6 Million tonnes per annum plastic waste is recycled (i.e. 15,600 tonnes of waste per day) and 3.8 Million tonnes per annum plastic waste is left uncollected or littered (9,400 tonnes of waste per day). Out of the 60% of recycled plastic: 70% is recycled at registered facilities, 20% is recycled by Unorganized Sector, 10% of the plastic is recycled at home.

The Government of India notified Plastic Waste Management (PWM) Rules, 2016 on 18th March, 2016, superseding Plastic Waste (Management & Handling) Rules, 2011. These rules were further amended and named as ‘Plastic Waste Management (Amendment) Rules, 2018. Altogether 18 States and Union Territories have taken initiative and imposed some kind of ban on plastic manufacture, stock, sale, or use of plastic carry bags, namely Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Chandigarh, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Goa, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand and West Bengal.

Successful case studies on plastic ban in India

i. Operation Blue Mountain in Nilgiris ,Tamil Nadu

Operation Blue Mountain campaign was led by Supriya Sahu, the District Collector in 2001 to ban the use of plastic in the district. The campaign was crucial to unclog the river sources and springs in the popular hill station of Nilgiris. The experiment has been documented by erstwhile Planning Commission and UNDP as the best practice on governance from Indian States. In order to make people understand, the campaign used pictures of choking animals. They also explained how plastic clogs drains and also seeps into the lake and other water bodies.

ii. Sikkim first State to ban Plastics Bottles & Disposable Foam Products

Sikkim, which is often applauded for being one of the cleanest states in India has now taken one more step to reduce its carbon footprint. In two recent notifications issued by the state’s home department, the Sikkim government has decided to manage its waste in a more efficient and eco-friendly manner by banning the use of plastic water bottles in all Government meetings and programmes. Further, it has banned the use of disposable foam products across the entire state.

iii. Maharashtra Ban on Plastics

Maharashtra will be the 18th state in India to ban single-use disposable plastic. Maharashtra has banned disposable products manufactured from plastic and thermocol (polystyrene). Maharashtra plastic ban carries penalties starting at Rs. 5,000 and goes up to Rs. 25,000 and 3 months of imprisonment. The government has played a major role by bringing in the law, mechanism of imposing it, the fines and the paraphernalia that goes with the implementation. Now, flower vendors are sending flowers to people’s home in cloth bags. Vegetables are being sold in cloth bags. Women in self-help groups are looking at making jute or cotton bags as a major source of income. Medicines are coming in small paper pouches. Tea and coffee stalls, college canteens and restaurants are doing away with plastics. Also, the corporates like Starbucks, Coca Cola and Bisleri have risen to the occasion and taken up responsibility of collecting waste plastics from Mumbai and recycle it or up-recycle it to different use. People participation can be seen as NGOs, schools, celebrities, industrialists have begun campaigns to beat plastic pollution.

iv. Himachal Pradesh Sustainable Plastic Waste Management Plan

The Government of Himachal Pradesh enacted the Himachal Pradesh Non-Biodegradable Garbage (Control) Act, 1995, to deal with the menace of plastic and other non-biodegradable waste. This Act embodied a move towards scientific disposal of non-biodegradable waste and also imposed a ban on coloured plastic carry bags produced from recycled plastic. The Government of Himachal Pradesh introduced the Sustainable Plastic Waste Management Plan in 2009. The Plan focusses on controlling the use of plastic and developing a systematic disposal mechanism. In order to achieve the objectives of its Clean Himachal and Healthy Himachal drive, the Government also prohibited the use of plastic cups and plates in 2011; conducted Information, Education and Communication (IEC) activities to generate awareness about the harmful impact of plastic waste, and encouraged citizens to stop using plastic products.

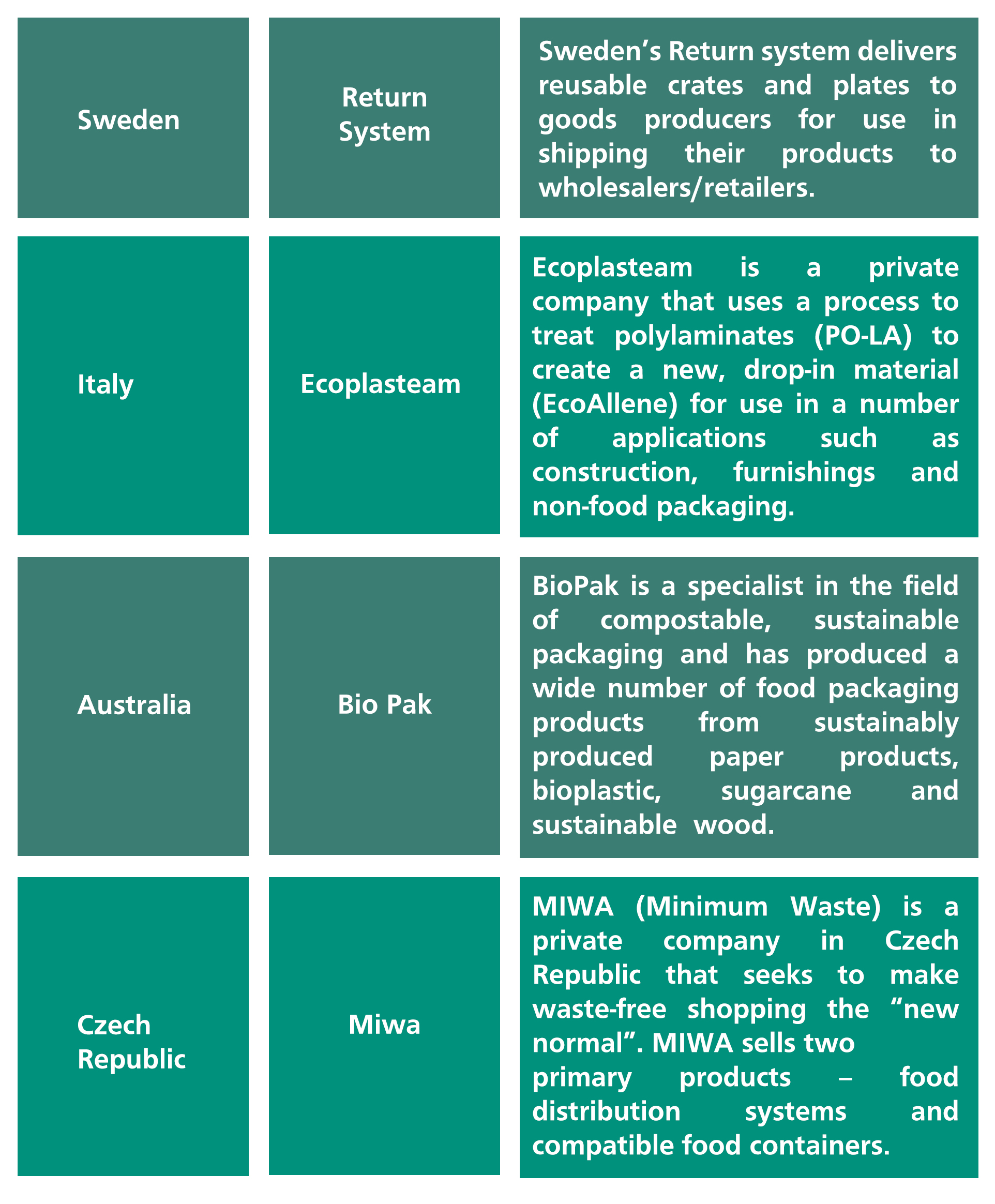

A cursory look at Public - Private initiatives to reduce single use plastic bags and Styrofoam products across the globe:

| AREA | COUNTRY | YEAR | ACTION TAKEN | TYPE | FEATURES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | Indonesia | 2017 | Government commitment | Memorandum of understanding | Type: Because of a four-year campaign organized by citizens to get plastic bags banned in Bali, the governor signed a memorandum of understanding to phase out plastic bags by January 2018 |

| Europe | Germany | 2016 | Public private agreement | Ban or levy | Type: Voluntary ban or levy on plastic bags (retailers can decide whether to phase out plastic bags or to apply a fee of €0.05 to €0.50 (about $0.06 to $0.60). The agreement was made by the Ministry, the German Retail Federation and participating companies to curb the use of plastic bags. In addition, many more companies participated without having signed the agreement. |

| Switzerland | 2016 | Public private agreement | Levy | Type: Switzerland’s largest supermarket chains introduced a plastic bag levy based on a voluntary agreement, which was approved by the parliament as an alternative to a total ban. Impact: Demand for plastic bags dropped by 80- 85% (Price tag., 2017). | |

| Luxemburg | 2004 | Public private agreement | Levy | Type: 85 brands (including all big distributors) participated in the “Eco-sac” (“Öko-Tut”) initiative, a cooperate project between the Ministry of the Environment, the Luxembourgian Trade Confederation and the non-profit association Valorlux to reduce the consumption of lightweight plastic bags by replacing them with the so-called “Öko-Tut” (a reusable bag). Impact: Plastic bag consumption dropped by 85% in nine years and the “Öko-Tut” has replaced most free plastic bags at supermarkets across the country (Luxembourger leads way, 2013). | |

| North America | Canada | 2016 | Private Initiative | Levy | Type: A big supermarket chain announced that it will start charging consumers CAD 0.05 (around $0.04) per single-use plastic bag and CAD 0.25 per reusable bag. |

| Oceania | Australia | 2017 | Private Initiative | Ban or Levy | Type: Some major supermarkets announced that they will phase out lightweight plastic bags or provide bags but charge AUD 0.15 ($0.12) per bag. |

Successful Case Studies on Plastics Ban across the continents

i. China: National and provincial policies: Prior to 2008, about 3 billion plastic bags were used in China every day, creating more than 3 million tonnes of garbage each year. Due to such large volume of plastic waste, plastic litter in China is now being called as “white pollution”. To curb the production and consumption of plastic bags, in 2008, the Government of China introduced a ban on bags thinner than 25 microns and a levy on thicker ones, promoting the use of durable cloth bags and shopping baskets. Exemptions were allowed for bags used in the handling of fresh food such as raw meat and noodles for hygiene reasons.

Impact: One year after the introduction of the legislation, the distribution of plastic bags in supermarkets fell on average by 70%, avoiding the use of 40 billion bags. Within seven years, the number of plastic bags used by supermarkets and shopping malls shrank by two-thirds, with 1.4 million tonnes of bags avoided. However, plastic bags do remain common, especially in rural areas and farmers’ markets, due to weak enforcement. China has recently (January 2018) introduced a ban on the import of plastic scrap.

ii. Costa Rica: Total Single-Use Plastic Ban: By being first to pledge phasing out all single-use plastic bags, Costa Rica has emerged as an environmental leader in many ways. It was successful in doubling its forest cover from 26% in 1984 to more than 52% in 2017. On 5th June 2017, World Environment Day, the government announced a National Strategy to phase out all forms of single-use plastics by 2021 and replace them with alternatives that biodegrade within six months. The ban aims at eliminating not only plastic bags and bottles, but also other items such as plastic cutlery, straws, Styrofoam containers and coffee stirrers. The Strategy promotes the substitution of single-use plastic through five actions: i. Municipal incentives, ii. Policies and institutional guidelines for suppliers, iii. Replacement of single-use plastic products, iv. Research and development, and v. Investment in strategic initiatives. In implementing this project, the government is supported by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), local governments, civil society and private sector groups.

iii. Kenya: Punitive total ban: Prior to 2017, about 100 million plastic bags were used in Kenya every year in supermarkets alone, impacting the environment, human health and wildlife especially in areas where waste management systems are inadequate. In Western Kenya, veterinarians claimed that in their lifetime, cows ingest a considerable amount of plastic bags, among other plastics. In February 2017, the Government of Kenya announced a ban on the production, sale, importation and use of plastic carry bags, which came into full effect after six months (in August 2017). Under the new law, representing the third attempt in the past decade, offenders can face fines of up to $ 38,000 or four-year jail terms, making Kenya’s plastic bag ban the most severe in the world. Before the law entered into force, UN Environment supported the organization of a stakeholder dialogue where national and local-level officials could engage with private sector representatives to exchange views on how best to implement the regulation. Large supermarket chains are selling reusable cloth bags, as the government encourages retailers to offer consumers alternatives to plastic bags. Kenyans are slowly adjusting to life without plastic bags but there is not yet a clear account of the impact of the ban. The government is now starting an analysis to measure the overall act of the ban. On one hand local ‘green’ businesses see this as an opportunity for new innovative solutions to succeed and prosper, on the other hand, during this transition period - where there is lack of affordable eco-friendly alternatives – hygiene and food loss concerns are being raised by small-scale vendors (selling for instance pre-cooked foods, fruits and vegetables in markets).

iv. Rwanda: In 2004, the Rwandan Ministry of Environment, concerned by the improper disposal of plastic bags, as they were often burned or clogged drainage systems, commissioned a baseline study which revealed that plastic bag litter was threatening agricultural production, contaminating water sources and creating visual pollution. In 2008, the Rwandan government banned the manufacturing, use, sale and importation of all plastic bags. Paper bags replaced plastic ones, and citizens also started using reusable bags made of cotton. Along with the new ban, tax incentives were provided to companies willing to invest in plastic recycling equipment or in the manufacturing of environmentally friendly bags. Critics claim that stakeholders were insufficiently consulted during the policy design and that the poorest fractions of the population were not considered. Despite good intentions, after the enforcement of ban, investments in recycling technologies were lacking, as there were good and cheap alternatives available. As a result, people started smuggling plastic bags from neighboring countries and a lucrative black market emerged. With time, enforcement of the law became stricter, and if caught, offenders would face high fines and even jail. In the long run, citizens became used to the new regulation and, Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, was nominated by UN Habitat in 2008 as the cleanest city in Africa.

v. Antigua and Barbuda: In January 2016, Antigua and Barbuda prohibited the importing, manufacturing and trading of plastic shopping bags. In July of the same year, the distribution of such bags at points of sale was banned, leaving enough time for retailers to finish their stocks. Since plastic bags sold in large retailers accounted for 90% of the plastic litter in the environment, the ban was first implemented in major supermarkets, and later extended to smaller shops. Key elements of policy’s success include four rounds of stakeholder consultations to ensure engagement and acceptance of the policy. Stakeholders engaged include major retailers, the National Solid Waste Management Authority, the Ministry of Trade and the Department of Environment. After approval by the Cabinet, it was decided that the ban would be incorporated in the existing legislation, as this was more expedient than instituting a new law. An awareness-raising campaign titled “I’m making a difference one bag at a time” included frequent television short clips by the Minister of Health and the Environment providing information on the progress of the ban and feedback from stakeholders. A jingle was produced to promote the use of durable bags for a cleaner and healthier environment. Moreover, shoppers were provided with reusable bags outside supermarkets, and seamstresses and tailors were taught how to manufacture such bags so as to meet increasing demand. Major supermarkets were also required to offer paper bags from recycled material, in addition to reusable ones. To encourage the manufacturing and use of alternatives to plastic bags, the legislation includes a list of materials that will remain tax free, such as sugar cane, bamboo, paper, and potato starch.

Impact: In the first year, the ban contributed to a 15.1% decrease in the amount of plastic discarded in landfills in Antigua and Barbuda, and paved the way for additional policies targeting the reduction of plastics. For instance, the importation of plastic food service containers and cups was prohibited in July 2017. As of January 2018, single-use plastic utensils were banned, as well as food trays and egg cartons. At a later stage, Styrofoam coolers are also expected to be outlawed.–

2.3. SAI Initiatives: When problem like this occurs across the globe at such an unprecedented scale, the auditor cannot do fence sitting watching as a mute spectator but proactively engage with the major stakeholders towards mitigation of crisis. In befitting response to crisis, the INTOSAI Working Group on Environmental Auditing (WGEA) adopted this topical issue into its Work Plan 2020-2022 to steer the project under leadership of SAI India. A WGEA survey on management of plastic waste conducted in 2020 as a part of this research project showed that out of the 40 SAIs which responded, 58 percent of SAIs reported existence of legislations/regulations/policies/guidelines for plastic waste management in their country and 40 percent of SAIs also have conducted audit work specific to plastic waste management. Some case studies are given below:

i. State Audit Office of the Republic of N. Macedonia: A performance audit on the topic “Efficient treatment and management of plastic waste” covering the period 2017 – 2019 was conducted and it was observed: a. Strategic, planning and program documents at central, local and regional level documents are not adopted and some are outdated posing challenges for setting up an Integrated Waste Management System. b. Lack of initiatives toward reusing plastic waste. c. Informal waste collection sector is not properly recognized in relevant legislation. d. Activities regarding management of plastic waste were neither sufficient nor efficient in prevention/reduction of plastic waste. e. Low level of awareness about plastic waste collection/segregation mechanisms signifying lack of implementation in educational/ information tools. f. Measures are not providing incentives for plastic waste processing. g. Apathy from manufacturers towards measures to extend the life cycle of products. h. Inefficient collection and transportation of packaging waste (selected waste). i. Inconsistencies in implementation of measures based on “polluter pays” principle. j. Absence of regulatory mechanism in respect of collective packaging waste handlers regarding collection and utilization of realized revenue. k. The amount of collected fees paid to the treasury account or to the collective packaging waste handlers is insignificant, indicating insufficient funding for encouraging activities for collection, transport, processing and disposal of packaging waste. l. Inefficient data collection system in respect of issued permits (export of plastic waste), collected, processed and deposited plastic waste. m. Insufficient monitoring mechanism for waste management at national and local level and the supervisory activities by competent institutions.

ii Supreme Audit Court of Iran (SAC): Supreme Audit Court of Iran (SAC) has used the pathology model in environmental auditing in the process of conducting audit of plastic waste management. SAC in this method examined the pathology of the mechanisms governing the ecosystem (policies and laws at the macro level) in a small range, and finally based on the findings and results of the audit offered recommendations for improving its environmental status. Pathology requires a systematic approach to the whole process and its purpose is to identify the nature and type of the problems that have arisen and need to be solved. In this model, damage is anything that interferes with the system in achieving its goal, or whatever that hinders the achievement of the goal. Pathology is the first step to get things done legally, prevent breaches of obligations and also deal with problems. It includes four stages of a. recognizing the nature and mechanisms, b. identifying harmful signs, c. rooting out the causes and factors of damage, d. finding solutions to deal with damage.

Conclusion: Based on performance and compliance audits conducted in relation to plastic waste during the last few years, SAI underlined the significance of constructive and promising measures in the field of waste management such as submission of a bill to reduce plastic bags (2019) for approval by the Islamic Consultative Assembly, building up a committee to reduce plastic consumption in the Environmental Protection Organization, increasing public culture regarding the nature and damages of plastic waste and, consequently, the activities of the public and their participation in plastic waste management. In addition, in order to increase the awareness of auditors, the Supreme Audit Court had compiled a book on waste audit and also by translating the experiences of other SAIs, tries to participate in training courses and conferences, share experiences with other peers and improve its status.

iii. Accountability State Authority (ASA), Arab Republic of Egypt: The Accountability State Authority (ASA) of Arab Republic of Egypt conducted an audit to evaluate the performance of the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency with regard to its process of plastic waste management operations in 2019 and recommended to: a. Strengthen legislation encouraging recycling. b. Encourage plastics recycling to become a recognized activity to develop the sector performance. c. Improve performance of Waste Management Regulatory Authority. d. Increase training courses for workers in this field to improve their skill. e. Oblige packaging manufacturers to put a label on the plastic packing material to facilitate the sorting process.

Government Actions: In June 2019, Government announced banning plastic bags usage & disposable plastic tableware in Marsa Allam & Hurghada cities. An “Environment” initiative was taken by the Government to raise awareness of reducing the consumption of plastic bags.

iv. United States Government Accountability Office (GAO): GAO was asked to review federal efforts that advance recycling in the United States. The performance audit was conducted from August 2019 to December 2020. The GAO examined (1) cross-cutting challenges affecting recycling in the United States, (2) actions that selected federal agencies had taken that advance recycling, and (3) actions Environment Protection Agency (EPA) had taken to plan and coordinate national efforts to advance recycling. Based on GAO analysis of stakeholder views, five cross-cutting challenges affect the U.S. recycling system: (1) contamination of recyclables; (2) low collection of recyclables; (3) limited market demand for recyclables; (4) low profitability for operating recycling programs; and (5) limited information to support decision making about recycling.

Conclusion: 1. EPA has not taken steps to implement Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) requirements to conduct studies and develop recommendations for administrative and legislative action about either existing policies or Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) requirements. 2. EPA’s draft national strategy does not align with desirable characteristics for effective national strategies. 3. Commerce has taken actions to advance recycling, in part by supporting export markets for U.S. recyclables. However, Commerce has not taken action to stimulate the development of domestic markets for recyclables, as we recommended in 2006. 4. Moreover, according to EPA officials, recent changes to the Basel Convention might further reduce export markets for plastic recyclables. Recommendation: To develop an implementation plan: a. For conducting a study and developing recommendations for administrative or legislative or eliminating such incentives and disincentives, upon the reuse, recycling and conservation of materials. b. Regarding the necessity and method of imposing disposal or other charges on packaging, containers, vehicles, and other manufactured goods to reflect the cost of final disposal, the value of recoverable components of the items, and any social costs associated with non-recycling or uncontrolled disposal. c. To incorporate desirable characteristics for effective national strategies, including (1) identifying the resources and investments needed, and balancing the risk reductions with costs, (2) clarifying the roles and responsibilities of participating entities, and (3) articulating how it will implement the strategy and integrate new activities into existing programs and activities.

v. The National Audit Office of the People’s Republic of China (CNAO): Objective : To investigate the implementation of China’s ban on imported solid waste, and the impact of the use of imported waste plastics on the environment, with a focus on the illegal transfer of import licenses for solid waste and final disposition of the imported waste plastics. Audit findings and audit methods applied: 1 Illegal transfer of import licenses for solid waste: a. Some companies import waste plastics in violation of the regulated quota and the requisite provisions. b. Some unqualified companies cooperate with qualified companies to apply for import licenses in the name of the latter, and make profits through direct reselling upon actual import of the waste plastic violating regulations of the Administrative Measures for the Import of Solid Waste. 2 Disposition of the imported waste plastics- Some companies use waste plastics as raw materials to produce packaging against regulations violating the regulations of the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China and other authorities.

3. Best practices for plastic waste management:

4. Circular Economy

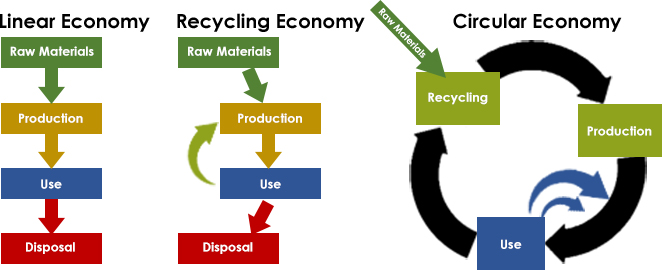

One way of handling plastic waste in efficient and productive manner is urge of the world community to move to circular economy from linear economy. The circular economy is a restorative and regenerative by design. This means materials constantly flow around a “closed loop” system, rather than being used once and then discarded. In the case of plastic waste, this means simultaneously keeping the value of plastics in the economy, without leakage into the natural environment. This can be achieved via long-lasting design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing, recycling and upcycling. The ultimate aim is to minimise the amount of resources consumed, and waste generated, by our economic activities. Circular economy approaches are also contributing to the implementation of the Paris Agreement and climate related targets, as well as the biodiversity targets.

In contrast, the linear economy aims at a “take, make, dispose” model of production, as illustrated in Figure below. Circular economy is market economy, new values should be introduced and therefore regulation needed besides markets. For example, oil is a very easy item to trade, while plastic waste is not. Therefore, circular economy needs to be made as efficient as the market economy because the outcome is better. A circular economy for plastic is necessary to limit consumption of plastic while ensuring that the plastic used is appropriately managed throughout its lifecycle.

Figure: From linear economy to circular economy

5. Way forward

Given the broad spectrum of possible actions to curb single-use plastics and their mixed impact, UN Environment has drawn up a 10-step roadmap for governments that are looking to adopt similar measures or improve on current ones. The steps are based on the experiences of 60 countries around the globe:

- Target the most problematic single-use plastics;

- Consider the best actions to tackle the problem;

- Assess the potential social, economic and environmental impacts;

- Identify and engage key stakeholder groups;

- Raise public awareness about the harm caused by single-used plastics;

- Promote alternatives;

- Provide incentives to industry;

- Use revenues collected from taxes or levies on single-use plastics to maximize the public good, thereby supporting environmental projects or boosting local recycling with the funds and creating jobs in the plastic recycling sector with seed funding;

- Enforce the measure chosen effectively, by making sure that there is clear allocation of roles and responsibilities;

- Monitor and adjust the chosen measure, if necessary and update the public on progress.

6. Conclusion

Adoption of Agenda 2030 has added a new dimension requiring SAI work to include SDG audits. Shifting SAI activities from “accountability for process” to “accountability for performance,” is becoming more important for improving accountability and efficiency in public governance. Growing emphasis are laid on the ideas related to circular economy, integrated waste management including recycling practices and stringent regulations for abatement of pollution caused by plastic. This subject has also emerged as a very relevant field of study by SAIs around the world in terms of sustainable production and consumption of plastic, its mismanagement, plastic waste and pollution caused by plastic. Unprecedented rate of production and consumption of plastic for economic and social progress has resulted in depletion of natural resources and adverse impact on environment, reaching a critical stage. With increasing demand and production of plastic, the extent of plastic waste and resulting menace has increased globally indicating unsustainable management of this valuable product. Plastic waste poses serious environmental, social, economic and health threats and its harmful effects on terrestrial and marine ecosystems have also become major global concerns. There is a clear upward trend in the number of public policy responses to the plastic pollution problem over the last decade, at global, regional and national levels, yet the risk remains seriously high. It is therefore imperative for the Governments to review their policies towards management of plastic waste. SAIs can examine the efficiency and effectiveness of measures taken by Governments in the respective countries. A transformative and circular economy approach covering the entire value chain from production of plastic to plastic waste management is needed to address the problem of mismanaged plastic waste in a comprehensive manner. Covid-19 has aggravated the problem as PPEs, masks and disposable syringes are made of plastic. This envisages the concepts of producing less, consuming less, adopting environmentally friendly techniques for recycling, upcycling, imposing legal instruments and proper disposal of waste that already exists to prevent contamination or leakages. Urgent actions are therefore required to be taken through involvement of numerous stakeholders in society including citizens, governments, community organizations, businesses, and manufacturers. Policy solutions, increased awareness and improved design and disposal processes, among others, can minimize the impact of plastic waste on society.

7. Recommendations

- The auditors should endeavour proactively with constructive approach for mitigation of global crisis by engaging themselves with the major state actors, civil society, private agencies etc.;

- Acquire domain knowledge of plastic waste management through skill development process to carry out compliance/ performance plastic waste audit effectively;

- Audit planning should be aligned with the UNGA’s 17 SDGs especially SDG 12 and periodical reporting on audit findings to national government for initiating corrective measures;

- Promote best practices across the departments and try to address cross cutting issues; and

- Recommend measures for people participation to be taken up by national governments across the globe in this holistic nature purging process which remains at core of all initiatives.

References:

- Plastic Waste Management, issues, solutions &case studies, March2019, Ministry of housing & Urban affairs, GOI;

- https://ourworldindata.org/faq-on-plastics ;

- UNIDO Report- Recycling of Plastics in Indian perspective by Dr. Smita Mohanty;

- Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016;

- UN Environment: Single Use Plastics- A Roadmap for Sustainability;

- 2017 strategy for a waste-free Ontario. Building the circular economy;

- Overview of Plastic Waste Management by CPCB;

- Auditing Plastic Waste: Research and Audit Benchmarks for Supreme Audit Institutions, INTOSAI, WGEA;

- The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2020;

- Plastic and Climate, The Hidden Costs of Plastic Planet, CIEL;

- Global Environment Outlook-6 Measuring Progress towards achievement of environment dimension of SDGs and Progress report;

- SAI India and https://sealive.eu/project-news-case-studies-on-circular-plastics