1. Introduction

The Board of Audit and Inspection (BAI) has strived to strengthen preventive auditing to help identify, predict, and respond to potential problems and crises in our society. In this regard, BAI conducted a series of audits which provided analyses and projections about the impact of demographic changes on key social sectors and sought for improvement measures in current responses. Amongst these, this particular audit focused on demographic change in rural Korea.

n Korea, the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) dropped below the replacement level of 2.1 in 1983, and has since continued to fall significantly for the last 4 decades. This demographic crisis is particularly intensified in rural areas with local governments expressing their concerns about villages “disappearing” altogether. It is believed that demographic challenges in Korea largely stem from two interconnected issues: a sharp reduction in fertility rate and overconcentration in capital areas.

2. Audit Theme and Approach

This audit presents the following questions: “How will the regional population change in the future if the current level of super-low fertility trend and urban centralization continues?”; “What are the causes of these phenomenon?”; and “How can the government policies be improved?”

In terms of audit approach, first, BAI made projections about the national population for the next 30, 50 and 100 years, in cooperation with Statistics Korea. Based on these estimations, BAI asked for assistance from the Korea Employment Information Service (KEIS) to calculate the Extinction Risk Index (ERI) in that time frame.

Next, BAI outsourced the research to compare TFR, rate of marriage, etc. based on the microdata from the Statistics Korea and to analyze the correlation between urban centralization and super-low birth rate.

Lastly, conducted a survey on 245 officials in charge of demographic policies in local governments nationwide to figure out the causes of low-birth rate as well as the problems of government policies.

2. Audit Results

(Summary) Super-low birth rate and shrinking regional population are linked with urban centralization. Younger generation in local areas are leaving the capital to find decent jobs while those in the capital are staying single or marrying late due to fierce competition and uncertainty about their future. BAI audited government policies on low birth rate and relocation of government functions to check if they have sufficiently considered ways of easing overpopulation in capital areas, and improve local conditions for education and working.

A. Long-term Estimation of Regional Population

Keeping the TFR of 0.98 from 2018 as reference point, BAI analyzed the long-term estimations in year 2017, for the 17 Si and Do as well as 229 Si, Gun, and Gu areas1. As a result, 13 Si and Do were found to be facing a population decline by up to 23% in 30 years, while 16 Si and Do are projected to see the maximum 44% drop in 50 years, and eventually all 17 Si and Do will experience the maximum 79% depopulation in 100 years.

On the other hand, by 2047 (30 years from 2017), an increase in population (by 6.2%) would be observed in the Gyeonggi Do district, while population in Incheon will exceed that of Busan2,deepening regional disparities even further

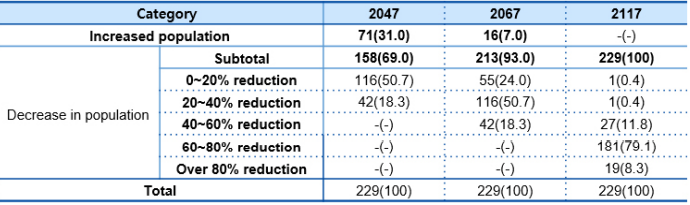

Looking at Si, Gun and Gu, 158 (69%) out of 229 districts will experience depopulation in 30 years (2047) while 71 districts will see an increase in population due to urban centralization, worsening regional disparity. In 50 years, 213 districts(93%) will lose a large proportion of its population while 16 districts will witness increased population. However, in 100 years, all districts will face population decline.

Long-term rate of change in population by Si, Gun, and Gu (Unit: district, %)

B. Regions with Higher Risk of Depopulation

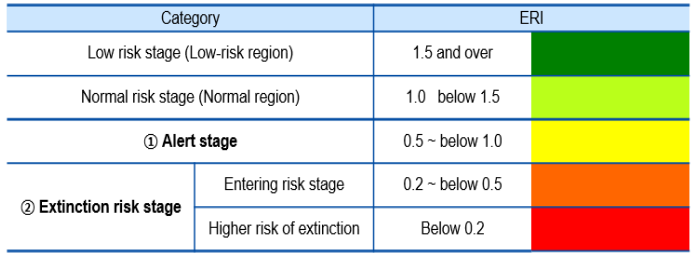

The Extinction Risk Index (ERI) comparesthe elderly population aged 65 and over with the childbearing female population between 20 and 39, in order to measure the ability of regions to sustain its population in the future. In this audit, BAI predicted that regional districts are at a higher risk of extinction.

1 Si and Do: Provincial-level divisions; Si, Gun, Gu: Municipal-level divisions.

2 While Gyeonggi Do and Incheon are located within capital areas, Busan is located in a non-capital area.

Extinction Risk Index

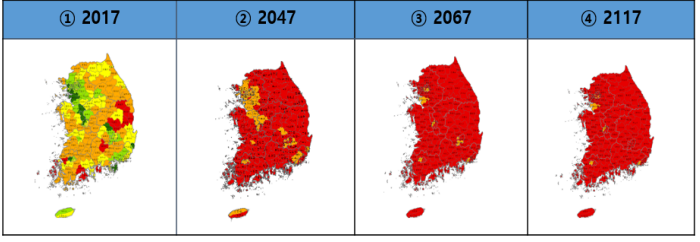

In the audit results, it was noted that all Si, Gun, and Gu areas will enter the extinction risk stage in 30 years(2047), which correspondsto ‘the declining stage’ in the demographic transition model. If there is no significant turning point, these districts are forecasted to shrink gradually.

Extinction risk regions based on population estimations

C. Younger generation’s migration to capital areas

It was predicted that even with largescale depopulation, the overconcentration in capital areas will further intensify, rising above the current level (of 50.1%). In particular, the concentration of younger population in urban centers will increase to about 54% by 2047, driving urban centralization.

Young generation’s migration to capital areas mainly stemsfrom the following: (1) When compared to regional universities, there are more high-ranking institutions in the capital areas; and (2) local regions have fewer types of jobs and the ‘decent’ jobs are concentrated in capital areas, as 73% of companies with total assets of KRW 5 trillion or more are located in capital areas.

D. Super-low Birth Rates in Capital Areas

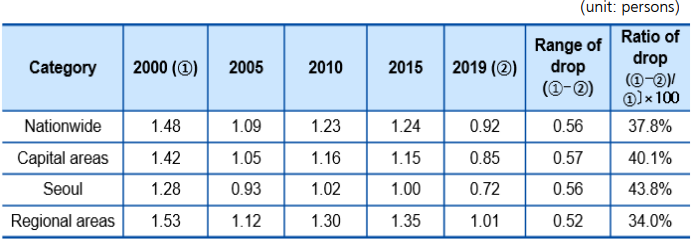

Although young people are concentrated in capital areas, urban TFR and marriage rates are lower than those of regional areas, which is deemed as the main driving force behind depopulation in Korea. TFRs of capital area and Seoul are lower than that of regional areas, and this difference is ever growing.

TFRs in capital areas, Seoul and Regional areas (2000~2019)

The audit intended to see if there is a correlation between high population density and low births and analyzed the key factors.

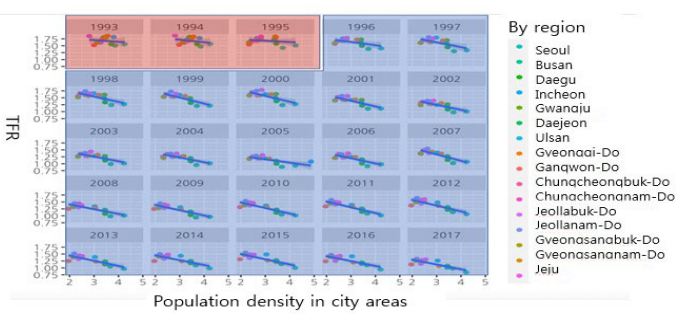

In urban areas of Korea (2005~2017), a strong negative relationship between the population density and the TFR could be observed. Othersocial and economic factors apart from population density,such as economy, housing, and jobs were also considered in the regression analysis. Among them, population density was found to have the greatest impact on the TFR.

Correlation between population density and TFR in urban areas (1993~2017)

- Highlighted area in red (1993~1995): No significant relationship, Highlighted area in blue(1996~2017): Significant relationship found

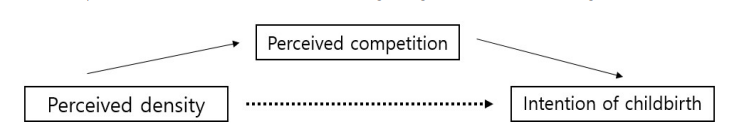

In order to analyze the impact of population density on the desire to have children, the audit verified the psychological process through 5 rounds of surveys. It was found that if an individual perceives a high population density, he/ she tends to perceive intensified competition, and therefore, attaches more importance to education and career, showing a negative attitude to marriage and childbirth.

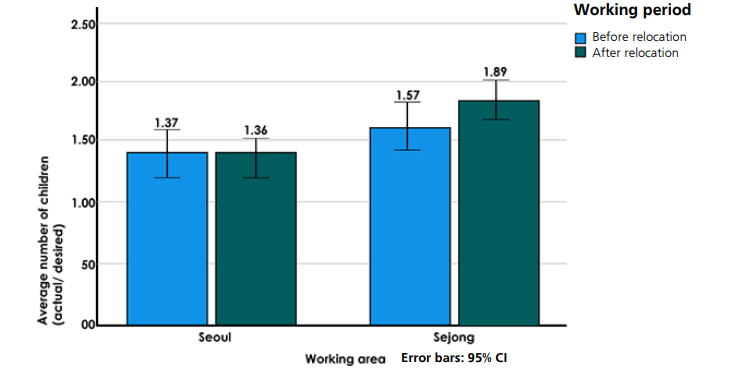

Also, the audit conducted a survey and analysis on central government officials working in Seoul and Sejong City3 in order to study the effect of changed population density on the fertility rate due to relocation. There was slight drop in the fertility rate (1.37->1.36) for officials working continuously in Seoul, whereasthe officials working in Sejong showed a higher fertility rate after (1.89) the relocation than before (1.36). The officials in Sejong displayed lower perception of population density and greater intention for childbirth.

E. Measures to Increase Policies Combatting Low-birth Rate

The Korean government established the Presidential Committee on Ageing Society and Population Policy (PCASP) in 2005, and has since implemented various policy measures to increase the number of births.

3Seoul is the capital city of Korea, Sejong City is a newly developed administrative city to mitigate population disparity between the two areas. Central government organizations were relocated to Sejong City in 2011.

Since its inception in 2004, the PCASP has developed three master plans, and implemented 292 projects in 18 different fields (total budget: KRW 262 trillion).

The PCASP measures to combat low-birth rate have increased the Marital Fertility Rate (MFR). It believes in shifting away from policies which only focus on providing young married couples with childcare help, and focus more on ensuring a social security net, ensuring couples are able to marry in the first place. There is also a need for improvement in settlement conditions in regional areas, especially considering that urban migration and intensified competition is the real reason behind the dip.

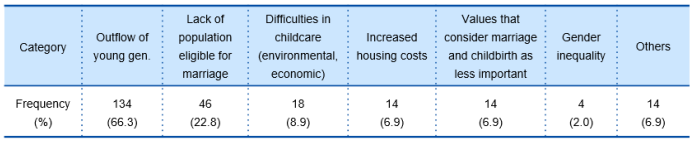

The audit conducted a survey on 245 officials in charge of demographic policies in local governments to find out the key measuresin place to increase birth rate, major reasonsfor urban centralization and countermeasures. Majority of the respondents thought that the outflow of young generation and resulting depopulation are the main reasons behind the low birth rate in regional areas. Also, they listed lack of decent jobs and quality education as the major drivers of this migration.

Major Reasons Behind Low Births in Regional Areas

Therefore, the PCASP needs to cooperate with related organizations including the Presidential Committee for Balanced National Development (PCBND) to support and manage relevant measures to improve education and job opportunities for the youth in regional areas.

F. Relocation Policies

Korean government relocated 153 public organizations from capital areas to regional areas in December 2019. 112 organizations (42,909 employees) moved to 10 “Innovative Cities.” 4

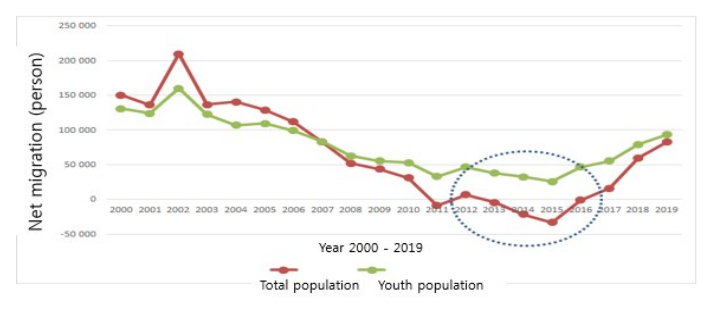

For the past twenty years, the net flow of capital population to regional areas occurred only between 2013 to 2015 during full scale relocation. At the time, 58,000 people moved to regional areas, but after completion, the inflow to capital areas grew again in 2016 and urban centralization kept intensifying (51.6% in 2020). The net inflow of young generation (aged 15 ~ 34) dropped between 2013 and 2015, but rebounded from 2016 onwards.

4“Innovative Cities” refer to 10 regional areas developed in order to relocate public organizations concentrated in capital areas.

Net migration of population between urban and rural areas (2000~2019)

The audit analyzed the inflow of population in 10 Innovative Cities, and found that a total of 196,538 people had moved in. When analyzing the net inflow population by region, the mother cities5 had the highest rate at 54%, followed by 23% in neighboring regional areas, while the capital areas accounted for only 15% (28,666 people)

The audit also inspected 18 former offices of the 13 relocated public organizations that submitted their relocation plans (with predictions on the expected benefits of relocation on population growth) to the government. Although 13 public organizations were relocated, a mere 6,560 people were transferred.

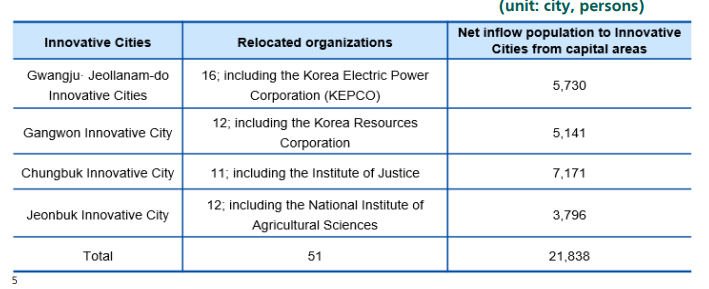

As a whole, the net inflow population from capital areas to 4 Innovative Cities only stood at 21,838.

Inflow population to 4 Innovative Cities from capital areas

The effects of relocation were limited because of (1) poor participation from private companies in the relocation initiative; and (2) insufficient efforts to establish and manage comprehensive plan to utilize the former offices.

As of late 2019, the number of private companies that relocated to the 10 Innovative Cities stood at 1,425, among which only 224 (15.7%) moved from capital areas. Total number of employeesin those 224 companies was at 3,422, which means each company hired only 15 employees on average.

According to Article 43 of the Special Act on Innovative City, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT) was supposed to establish plans to effectively utilize these buildings. Yet, the audit found, by reviewing major plans since 2003, that no specific plans were put in place.

Also, Article 34 of the Special Act on Innovative City stipulated that the relocation should be financed by selling the former offices. However, the audit found that 12 organizations, changed the registered purpose of the buildings to sell them at a higher price (building in green belt zone → residential/ commercial building), ironically leading to real-estate development in the capital areas- which in turn increased population.

3. Audit Recommendation

BAI recommended the PCASP and the PCBND to adhere to the following:

1) As low TFR lingers and the youth continues to migrate to capital areas, it is forecasted that Korea shall experience a dramatic reduction in total population and ageing, as well as possible regional extinction at a rapid pace.

In thisregard, the audit concluded that profound comprehensive measuresshould be needed through government-wide cooperation (PCASP, PCBND, central and local governments) to address regional disparities in population.

2) Public organizations have been relocated to regional areas to ease overpopulation in capital areas and promote development tailored to each region. However, very few private companies participated in the relocation, and no comprehensive plans were set up to utilize the public institutions’ former offices. Therefore, the relocation initiative not as successful. Also, the former offices were used as facilities to attract more population and employment, resulting in stimulating urban population growth instead.

In this context, proper relocation of private companies is in order. Also, their former offices should be put to proper use, without undermining the goal of rural population growth. To this end, government-wide efforts (by PCBND, PCASP, central/ local governments) are needed to implement in-depth balanced national development policies in tandem with demographic policies.