Mr. Ramawatar Sharma

Accountant General (Audit-II) Rajasthan

Mr. Ramawatar Sharma

Accountant General (Audit-II) Rajasthan

Public Procurement constitutes the process through which a government acquires goods, works, and services to meet its developmental and operational needs. Public Procurement accounts for a significant share of public spending; therefore, it directly impacts a country’s economic growth, service delivery, and governance outcomes. Globally, procurements are estimated at US$9–10 trillion a year. Given the vast scale of procurement activities, ensuring transparency, efficiency, and fairness is critical to safeguard public funds and build trust among stakeholders. However, procurement systems often face challenges such as inadequate competition, procedural irregularities, collusion, cost overruns, and risks of corruption or favoritism. Nearly 10-25 per cent of the value of public contracts is thought to be lost to corruption, inefficiencies or mismanagement.

In this context, public procurement audits play a vital role by delivering independent oversight, promoting accountability, and enhancing value for money in public expenditure. The true effectiveness of procurement audits lies not only in uncovering irregularities but in generating actionable insights into systemic lapses and recommending practical reform measures.

(a) Global Regulations: At the global level, instruments such as the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Model Law on Public Procurement (2011) (UNCITRAL, 2011) and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA) (WTO, 2014) set widely recognized standards for transparency, fairness, and competition. The INTOSAI Working Group on Public Procurement Audit (WGPPA), established in 2016, promotes knowledge sharing among Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) and develops standards and methodological guidance on auditing public procurement. Its key objectives include fostering the exchange of experience, creating professional pronouncements within the INTOSAI Framework of Professional Pronouncements (IFPP), and producing methodological documents to improve the use of budget funds in procurement.

(b) Public procurement and Sustainable Development Goals: Public procurement is a key driver in achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The 2030 Agenda explicitly recognizes its role under SDG 12.7 , which calls for promoting sustainable procurement practices in line with national priorities. By integrating sustainability into procurement policies, governments can support multiple goals—such as SDG 13 (Climate Action) through green procurement, SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by encouraging fair labour practices, and SDG 5 (Gender Equality) by promoting women-led enterprises.

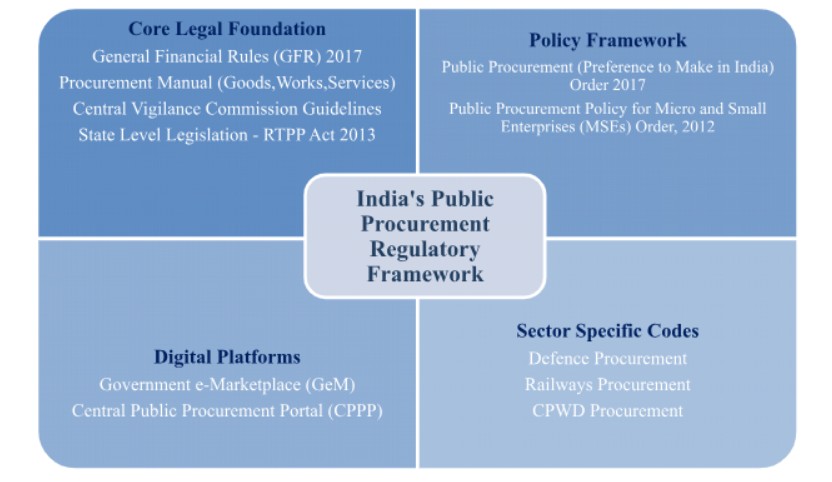

(c) Regulatory Framework in India for Public Procurement: India’s public procurement framework is anchored in the General Financial Rules (GFR), 2017 and supported by detailed Procurement Manuals for goods, works, and services along with Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) guidelines. Policies like the Public Procurement (Preference to Make in India) Order 2017, and the Public Procurement Policy for Micro and Small Enterprises (MSEs) Order, 2012 promote domestic industry and small enterprises. Several sectors (e.g.- Defence, Railways, Central Public Works Department (CPWD)) follow their own procurement codes, while states such as Rajasthan have enacted laws like the Rajasthan Transparency in Public Procurement (RTPP) Act, 2012. Digital platforms—Government e-Marketplace (GeM) and the Central Public Procurement Portal (CPPP)—have further strengthened transparency and efficiency.

(d) Public Procurement Process: Procurement in India is decentralized, with line departments and local bodies handling planning, tendering, evaluation, and contract management under central/state rules, e-portals, and treasury systems. At the district level, District Collectors and Zilla Parishads (District Councils) handle procurements through tender committees and departmental units, under treasury control and state oversight. Moving further down, at the block level, Block Development Officers (BDOs) manage procurement related to flagship programmes such as Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREG) supported by block-level technical and finance committees. Finally, at the village level the Gram Panchayats (village level elected bodies) undertake small-scale procurements for community works, where transparency is promoted through social audits, wall disclosures, and Local Fund Audit mechanisms.

To strengthen efficiency and transparency, the Government introduced two platforms- Government e-Marketplace (GeM) and Central Public Procurement Portal (CPPP). GeM is a unified online marketplace where government entities make direct purchases of goods and services from vendors. It enables better price discovery, reduces the scope for corruption, and provides a level playing field for businesses, especially SMEs and startups, to sell to the government. Further, CPPP is a platform for managing the tendering process, including publishing tender notices, managing bid submission, and tracking tender status. It streamlines the procurement process, reduces costs and ensures a wider reach of tender enquiries. GeM and CPPP systems are integrated into a single Unified Procurement System (UPS), offering buyers and sellers a consolidated experience for various public procurement needs.

Oversight on the procurement process is exercised through audits carried out by the SAI, complemented by government-led social audits and vigilance mechanisms under the Central Vigilance Commission. The state-specific rules and simplified local procedures shape variations at the grassroots level. Good practice signals include transparent policies, e-procurement with audit trails, explicit powers, vendor databases, robust audits, and public disclosure

Transparency is widely recognised as a precondition for accountability in procurement systems. Lack of openness enables collusion, bid-rigging, and undue influence, resulting in inflated costs and substandard outcomes. Conversely, transparent processes stimulate competition, enhance supplier confidence, and provide citizens with oversight opportunities. Audits serve as a corrective mechanism where transparency deficits exist. By exposing irregularities, publishing findings, and recommending reforms, they not only deter misconduct and corruption but also encourage competition and ensure compliance with the International Standards. Moreover, public disclosure of audit outcomes strengthens citizen trust and reaffirms the government’s commitment to stewardship of public funds.

The notion of Value for Money (VfM) in public procurement is not confined to securing the lowest-priced bid; rather, it entails a holistic evaluation of procurement outcomes. VfM is commonly assessed across three interrelated dimensions. Economy reflects the ability to acquire resources at the least possible cost while preserving quality standards. Efficiency emphasises deriving maximum output from available inputs. Effectiveness measures the extent to which procurement objectives are achieved and deliver sustained benefits. Procurement audits play a vital role in balancing cost with quality, timeliness, and long-term impact, ensuring public funds are utilised in a manner that advances both accountability and development goals.

A well-designed procurement audit typically follows a structured approach as under:

(a) Desk Review: Collection and analysis of procurement policies, contract files, and e-procurement data; creation of a guard file.

(b) Risk Profiling: Identification of high-value or high-risk contracts considering aspects such as single bids, repeat awards, or cost escalations.

(c) Field Verification: Examination of tender evaluation, contractor’s performance, delivery records, and payment vouchers.

(d) Criteria–Condition–Cause–Effect Analysis: For each audit finding, the benchmark (criteria) is specified, the deviation (condition) is described, reasons (cause) are identified, and consequences (effect) are analysed.

(e) Systemic Assessment: Beyond isolated cases, auditors seek to determine whether deficiencies reflect broader weaknesses in planning, oversight, or control systems.

Such an approach ensures that audit findings are evidence-based, analytically sound, and carry a good assurance value for decision-makers.

(a) UK National Audit Office (NAO): NAO’s thematic work on ‘efficiency and competition in public procurement (2023–2024)’ examined central purchasing, competition, and frameworks, identifying risks where over-reliance on frameworks or limited open competition reduces VfM and transparency. These reports emphasise the need for central oversight and better contract registers to save public funds (National Audit Office (NAO).

(b) Netherlands Court of Audit: The audits of ‘vaccine procurement and pandemic procurement arrangements (2020–2024)’ highlighted preparedness, transparency in emergency procurement and governance lessons for future procurements. National SAI case studies show a similar focus on emergency/health procurement, procurement data quality, and contract governance (Netherlands Court of Audit).

Public Procurement Audits carried out by the SAI India during the last five years

SAI, India offers rich case studies of procurement audit practice. Recent reports illustrate both achievements and shortcomings. Some of them are as follows:

Procurement auditing, despite progress, continues to face challenges such as missing documentation, query-driven approaches dependent on auditee data, risks of corruption and collusion, biased specifications favouring bidders, and difficulties in analysing large-scale e-procurement data, all of which undermine transparency, independence, and effective oversight.

To strengthen procurement oversight, SAIs is adopting innovations such as data analytics/AI for anomaly detection, e-procurement audit modules for direct data access, cross-verification with other agencies, systemic thematic audits of key sectors, and stronger peer review mechanisms—enhancing efficiency, credibility, and policy impact of audits.

The future of procurement audits lies in moving from fault-finding to system strengthening by focusing on systemic weaknesses, criteria-based analysis, and dissemination of best practices. This requires continuous auditor capacity building, adoption of advanced technologies (data analytics, blockchain, AI), robust follow-up on recommendations, and international knowledge sharing to enhance transparency, accountability, and global harmonization in procurement auditing.